Description:

e x c e r p t

Lesser Angels

Ken Hensley

Stillness. It was the stillness of the room that rattled me the most. Ten days of machines bleating and alarms sounding and now it was quiet. Almost peaceful. No, it was peaceful. And that rattled me even more.

We didn’t have a chance to talk. Once I arrived from the west coast they had already placed the breathing tubes down her throat. After seventy-nine, almost eighty years of endless chatter – never meeting a stranger – she was reduced to writing her thoughts on a note pad.

Never one to be diplomatic, she scribbled out: “Did you come here to watch me die?”

She knew for me to juggle my plans and fly in from California meant that the situation was serious. No one really knew what was going on. No one had diagnosed what had caused her kidneys to shut down. No signs of cancer, no blockage. Nothing out of the ordinary, with the exception of the tubes and wires and the other required things to keep a person alive.

“Did you come here to watch me die?”

How do you answer a question like that? The truth was, I had come there to watch her die. The way she snapped the pencil against the paper told me she already knew the answer. The tubes may have throttled her voice but they hadn’t dampened the fire in her eyes.

3:16 on a Tuesday afternoon. That was when it all became silent.

It had been nearly a year since my last visit. After moving west, my trips back to Illinois became less and less frequent. Too cold at Christmas and too muggy in the summer. How in the world did I ever enjoy growing up there?

Even though I joked about “Peoria in my rearview mirror,” there was much I appreciated about it. The people were good, honest, hard-working people. The type of folks who bought a house and never traded up. They just stayed put. And most of their kids did, too.

Somewhere in an old scrapbook is a picture of our third grade class visiting a local restaurant. Only the Peoria Journal-Star would run a story like that. Maybe it wouldn’t today, with the competition for eyeballs more fierce with the arrival of the Internet. But back in 1972, it splashed the story and photo above the fold, three pages in.

We had the local skating rink, complete with the mirrored disco ball in the middle. We did the limbo on skates and played shoot the duck. Every now and then we would head to Pekin, a neighboring town, to a skating rink known back then as the Chink Rink – complete with a Chinaman logo emblazoned on the wall. They changed the name just about the time that Archie Bunker went off the air.

Those were simpler times, far removed from my life in California.

When it came to playing sandlot football, everyone wanted to be on Danny’s team. You’d hand him the ball and let him run. He wasn’t fast. He was big. Each year I grow older adds another person hanging off his back as he plodded towards the end zone.

The last I remember of him, we had settled in with different crowds. In high school I was a geek, a few years removed from becoming a pastor. He was a stoner, a few weeks away from his first bump with the law. We didn’t play too much sandlot football during those days.

Honestly, I’m very thankful for my roots, my hometown. As much as I tried to think otherwise as a young twenty something, it’s a part of who I am. Cat diesel power and all.

As quickly as the silence came upon us, the pale blue room came to life again. Only this time, the busyness was more perfunctory in nature. It was doing the things that had to be done. Unhooking tubes, resetting machines, wiping things down with those swabs of cloth that reek of rubbing alcohol. Nurses came in and offered canned condolences. Thank God someone turned off the television.

“Did you come here to watch me die?”

It had been three or four days since she had asked the question. I tried to duck and dodge, but she wouldn’t have it. For someone paid to deal in words, I was having the toughest time coming up with something, anything. I had nothing.

So I told her the truth. I told her that I had come to watch her die.

##########

Sorting through the belongings of a dead parent took me back to the seventh grade, that time when I discovered certain curves on a female classmate and felt ashamed when she caught my eye. But not so ashamed as to not look again. The thrill of discovery mixed with the fear of being found out – a strange but delicious place to be.

It had been nearly eight years since my father had passed away. At that time, my sister and I had to shepherd mom not only through the grieving process but the paperwork as well. Bills and account statements tucked in between books. An address of a stockbroker in his sock drawer. We spent our time contacting insurance companies and HMO’s and retirement funds.

“But what are we going to do with his clothes?” my mom asked, peering around one of the stacks of paper that had accumulated on the counter.

In my mind, the big question wasn’t a matter of what but of whom: Goodwill or the Salvation Army? Mom didn’t want to see “nice shoes like that” leave the family. I didn’t have it in me to be a one-man crusade to bring wingtips back in style. Since dad often shopped at thrift stores, I made the theological case that it was a matter of ashes to ashes, dust to dust. The circle of life for polyester shirts and ugly neckties.

But that had been eight years ago and most of our energies were poured into looking after mom. We still had that gray-haired chatterbox who sat across the table from us and made sure we consumed mass quantities of mountain grown Folgers coffee. Folgers had long since abandoned the metal can, but the memories of how it was used in our house will live forever.

But as Rita and I sat around this same kitchen table, coffee upgraded to Starbuck’s Sumatra, we weren’t looking after mom. We weren’t helping her understand the difference between a money market and a mutual fund. Except for a few pictures and keepsakes, most of dad’s stuff had been removed eight years ago. She had come from Atlanta and I from San Diego. We both had come back to Peoria. Unlike eight years ago, we came back to an empty, quiet house.

That first night back, after the funeral and the last of the well-wishers, we found the old glass percolator and a can of mountain grown Folgers and brewed a pot to mom’s memory. It would be the last pot of Folgers but the first of many pots of coffee.

##########

“Why in the world do you think she kept this?” Rita was obviously concerned, perhaps a bit flummoxed, about why mom had kept a paper doodle Rita had made while talking on the phone to a boyfriend in high school. There was nothing suggestive or lewd about it; the embarrassing features were hearts with arrows and names and curly Q’s. Why THAT boyfriend, Jim or John or Joe, not sure, after all it was a LONG time ago. He had held Rita’s attention and interest for only a few weeks, maybe a month at best. For whatever reason, the lover’s doodle had made its way into a drawer in mom’s dresser, along with other potentially embarrassing but harmless items.

Rita and mom had one of those unusual relationships. Born three years after me, Rita could wrap my dad around her finger with a bat of the eye or a curling of the lip. She could just as easily engage my mom in a verbal war, with both sides tossing lyrical flamethrowers and run-on grenades. All sense of proper grammar was lost when the two Ferguson gals got heated up.

It didn’t take much. It could be a look taken the wrong way or a certain tilt to the tone of voice. One minute you’re reading Mike Royko in the Journal-Star and the next you’re ducking for cover under the kitchen table, waiting for that chance to grab your coffee before it gets swiped off the table.

Looking over at the paper with Rita’s hand-drawn love strokes, it reminded me of

when Rita was getting ready to head out with some girl friends of hers. She must have been fourteen or fifteen, not quite old enough to drive. She parked in the bathroom for a good fifty minutes. Fifty minutes of adjusting this strand of hair, dabbing some shade of red rouge on her cheeks and spreading it around with her finger. First one perfume, then another. Spraying her hair. Then spraying it again. Her hair alone required two bottles of hairspray. Until finally I was glad no one smoked in our house – it could have been fatal.

After the fifty minutes of primping and priming, she emerged with the look of a person who had just conquered her greatest hurdle and was taunting fate into throwing something harder her way. That would have been mom.

“Are you going out looking like that?” The way mom inflected and drew out four letters was actually quite amazing. Combined with two eyebrows that formed the not-so-golden arches, you would have thought that Rita was dressed in some kind of hootchie-gootchie outfit. If this had been the Sixties or Seventies, it might have been possible. But this was 1984 and she was in boot-cut jeans and a simple blouse.

What I think mom was trying to say, but didn’t quite put it the way she wanted to, was, “It took you fifty minutes to look like that?” Fifty minutes in the only bathroom in the entire house. Fifty minutes and two hairspray bottles. A near toxic combination of fumes and flavors and that’s it, that’s what you look like?

It wouldn’t have mattered. Either way, it was going to be fifteen more minutes of a different kind of fuming, just as toxic but more entertaining.

Perhaps they fought the way they did because they were so much alike. Add a

little color with Photoshop to mom’s teenage pictures and you’d have Rita with a bouffant and loafers. The curve of the cheekbone, the way they said “Worshington” instead of “Washington.” Amazingly, mercifully, both survived those years without any broken bones or irreparably damaged psyches.

I often thought Rita became a therapist because of those knockdown, drag-out fights. “You called him a sorry sack of humanity, but how did that make you feel?”

##########

Things. We collect things. We store things. We hide things. Life and three bedroom houses are filled with things. After my parents vetoed my idea of converting the basement into a walk-through museum, my next proposal was to bury a time capsule in the back yard. To bury things. Things for people to see and for future scientists to study.

Rita and I had begun in earnest our tour de force through the house. We only had a few days before jobs and families and the things of life beckoned us home. The therapist and the pastor mapped out an almost military like strategy, a strategy any parent of two or more kids would understand: divide and conquer.

After dad died, finding account statements amounted to a two-person search and rescue effort. Shoe boxes, books, behind the chest of drawers, under a keyboard. After a few days of playing private investigator, we decided our next best move would be to wait. If someone wanted money from us, they would send us a bill. And then it would get added to the list.

Since I had never fully shaken off my geek status, and given the fact that I had

brought my laptop with me, I was assigned the task of compiling lists and spreadsheets. It was eight years ago revisited, only this time we had to pay the bills. Find the bills, pay the bills. It seemed pretty straightforward, but only to the uninitiated in the ways of the Ferguson household.

Rita assumed the role of cleaner and diviner. As she swept through each room, she would make a snap judgment about what to keep and what to give away. At first, the pace is painfully slow. Your eyes spot a handmade frame that dates back to the days of the Partridge Family. Inside the frame is a drawing that somewhat resembles a tree or a frog, you can’t quite tell.

Keep it or toss it? How can you toss something you that cost you the better part of a Saturday afternoon, a masterpiece! Crafted with the pure, unadulterated love of a child. Then again, you’re not quite certain it’s something you did. Maybe it was your brother. Maybe your parents bought it at a garage sale. Maybe your parents didn’t care who painted it, it just belonged.

To keep it doesn’t make any sense. And besides, it’s only the first of hundreds, if not thousands of things just like it. But to toss it into the trash next to the McDonald’s sack and coffee grounds? With the first two or three it nearly causes an existential break down. After five or six, whatever emotional angst you might have been experiencing has been replaced with the resolve to get finished before Christmas. And this was in June.

##########

Three years and a few thousand miles separated Rita and myself. To say we had taken different life paths would be like saying that Yoko Ono broke up the Beatles –

something so obvious it goes without saying.

Her boyfriend de jour was a plastic surgeon that made his living giving boob jobs to Baptist gals. In southern church language, Dr. Stefan Spencer was on a mission to uplift the downtrodden. Some of the more unfortunate (but wealthy) had to be uplifted more than once.

I had never met Dr. Stefan, never hoped to actually. By my estimation, they had approximately another three or so good months followed by a week of “I’m not sure’s” and then a few days of “maybe it’s me’s.” Then the grand finale. True to the spirit of Neil Young, Rita always believed it was better to burn out than it was to rust.

Before the flesh peddler had been a steady succession of financiers, college professors, and the occasional construction worker. Rita had a discernible pattern. Two or three white-collar, starched shirt types followed by a three-day weekend with a construction worker or a clerk from Auto Zone.

Most of the men she dated, and a few of the ones she married, weren’t awful, despicable people. Most had no visible piercings. None were violent or otherwise abusive. They didn’t surface on any sex offender’s list. Most were just bland. Boring. For some reason, when it came to love, Rita – the free-wheeling, open to anything progressive liberal – always fell for type of guy who was, well, predictable.

At first, the promise of security and stability and nice looking children was enough reason to explore further, to see “if anything might be there.” Maybe he’s not so boring, she would tell herself. Maybe there’s a hidden layer, a wild side, to this member of the Cobb County Republican Party. Back in college, that alone would be a deal-

breaker. But a biological clock trumps ideals nearly every time.

Her longest relationship, in fact her longest marriage, had been to Sidney MacDonald. Employed for nearly twenty-five years with the Fulton County Sheriff’s Department, Sid was a good old boy from Macon who had entered police work right after high school. Rita had met Sid after a rather explosive grand finale with a podiatrist who worked at a clinic near Grady Memorial Hospital.

I once asked her on the phone, “How can you hold hands with someone who touches feet all day long?” How romantic could that be? I’d be thinking about all the scraggly, mangy digits he had to pick through, rubbing away bits and pieces of toe jam. Was he morbid enough to collect it all? How many times had he said, “and this little piggy went to market”?

Unlike the podiatrist and Dr. Stefan the Baptist missionary, I liked Sid. As a crime scene investigator, he could dial up a story in seconds flat that would have you ready to toss your groceries. The best part was the wicked humor these guys developed to deal with depths of human depravity.

“One time I get called out to a rave club near underground Atlanta. Next door is Monique’s Beauty Salon. It’s 2:30 in the morning. In the window of the salon is this mannequin’s head with one of Monique’s better styles. One cop, an old grizzly, picks up a severed hand, looks at the window, and says, ‘Well, all we need now are a few other body parts.'”

From the look on Sid’s face I could tell it was one of those “you had to be there” moments.

Sidney MacDonald had seen real bodies mashed and reassembled. Just when he thought he had seen it all, he hadn’t seen it all. There was something more. A deeper division between good and evil. A new low.

The cop and the therapist. Both probing the mysteries of human behavior, both looking for clues. They called it quits nearly three years to the day they were married. No kids, no house, no protracted divorce battles. There are still times I miss Sid.

##########

Our strategy of dividing and conquering was working quite well. The living room had been no match for Rita. Her powers of divining becoming sharper with the minute. Since most of my heavy lifting was over, thanks to wonders of an Excel spreadsheet, I decided to be brotherly and pitch in with Rita.

We turned our attention to the spare bedroom upstairs. It had become a spare bedroom when I left for college. Stepping into the room felt like I was slipping back to the late 70’s. Where was my Frampton Live album?

Other than chasing off the dust bunnies, mom and dad had left the room pretty much in tact. Books, posters, a potential fortune in baseball cards in the closet. It was all there, just the way I left it twenty-five years ago. I half expected to turn on the TV and hear Walter Cronkite sign-off the evening news.

After our walk down memory lane, it was time to tackle the last remaining bedroom – the bedroom that mom and dad had shared for nearly thirty years. Like I said, people in Peoria tended to buy a house and stay put.

Technically speaking, this would probably be considered the master bedroom.

The house had began as one of these experimental basement houses in the 1950s, back when surviving an atomic bomb was a very real concern to many people. It didn’t take too many months living in a basement for the original owner to decide he could probably just as well survive an atomic attack above ground as he could underground. My parents bought the house and moved us in not long thereafter.

Two bedrooms and a bathroom shared the same hallway, just off the kitchen and living room. Rita and I sat down on the bed where we had spent many a Saturday morning burrowed in between our parents, in the pre-digital, pre-cable days of television. The RCA set on their credenza picked up public broadcasting better than the one with the UHF knob in the living room.

Next to the lamp on the nightstand was a stack of McCall magazines and a menagerie of cassette tapes, pens, and post-it notes. For a fleeting second I thought I saw a box of Pall Mall cigarettes.

A chest of drawers dominated one corner of the room. On top of that sat the television that had replaced the RCA. No more bunny ears; my parents had succumbed to cable television after I went off to college. In fact, I think I passed the cable guy as I was backing out of the drive way.

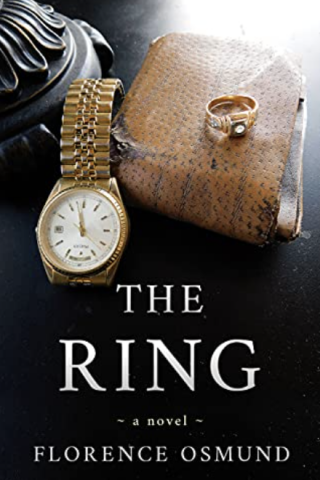

The dresser was also topped with a variety of jewelry boxes and trinket holders. We decided to start there. Clean off the top and work our way down through the drawers. The jewelry boxes only confirmed what we already knew: dad wasn’t the only one who enjoyed a visit to the thrift store.

Since Rita wasn’t into the retro haute look, we added them to our pile of

giveaways.

I pulled out the top drawer but pulled it too far and spent the next five minutes trying in vain to put it back on the track. After a not-so-valiant effort at re-engineering, I decided the more pragmatic route was to remove it completely and place it on the bed. Inside the top drawer were an odd collection of socks, shirts, and an assortment of pictures and papers. The undergarment drawer I would leave for Rita to handle.

Rita didn’t want to tackle the underwear either. Instead she dug a path into the closet, tossing aside shoes as she went. Near the back of the closet she found an accordion-style box, the kind that slides out drawers as you pull it open. A faint floral print was barely visible on the peeling sides of the cardboard.

The top level of the box, the smallest of the three layers, had old Polaroids of mom and dad, much younger and without kids. Dad had sideburns even back then. At a diner, in front of grandma’s house. Holding hands! They never held hands in front of us kids.

My parents had met after dad returned from World War II in the Pacific. Through a mutual friend, they met one Saturday afternoon at a pie auction. For the uninitiated in the ways of Southern Baptists, a pie auction was the cousin to having dinner on the grounds. At a gathering of Baptists you were likely to have an offering and food. In that order.

Dad had returned from the war older, chiseled, and determined to never to talk about what he had seen, what he had done. The war had destroyed families and created empty holes where many a man’s soul and spirit used to reside. If my father had been an

out-going free spirit prior to sailing into the Pacific sun, you never would have known it thirty years later.

Other Polaroids showed signs of a happy courtship. Rita and I had never seen most of these pictures before. Of the crooks and crevices we had discovered during hide and seek, mom’s closet had been off-limits. Not so much due to any imposed restrictions as much as for the shoes.

“Oh, my,” followed by a “no way.” Then “it can’t be.” Topped off with a loud whack, the sound of Rita’s head slamming into the wall. I waited for an “ouch” or at least a grunt, but it never came. I tossed a pair of mom’s socks into the closet and asked her what she found.

“You’ve gotta see this.” So I waited for Rita to emerge from the stacks of shoes. She didn’t budge. Poking my head around the corner of the sliding door, there was Rita, her head still pressed against the wall. Her face a whiter shade of pale.

I went in on hands and knees, careful not to disturb the path Rita had cut through the shoes. The pointed end of a red pump slammed into my shin. “For cryin’ out loud.” I wasn’t sure which was more traumatic – the pain shooting up my leg or the thought of mom in red pumps. Good Lord, let those have been from her younger days.

I looked up at Rita, hoping for a sympathetic recognition of my pain and there was none. Her eyes were glued to a yellowed piece of paper that kept bouncing up and down in her shaking hands. What could it be? A picture of mom in those red pumps? It was reassuring to know that the pain in my shin hadn’t throttled my sense of humor.

I would need all of that and more.

##########

Beneath the county seal was a Biloxi, Mississippi address. In all caps across the top of the page it read:

CERTIFICATE OF DIVORCE

##########

Biloxi, 1943.

Beauvoir stands as a grand accolade to the failed southern secession. The house features a wrap-around porch where Jefferson Davis once strolled, whiskey in one hand and a copy of the King James Bible in the other. The whiskey came in handy following the South’s surrender to Union forces.

It was at Beauvoir that Davis wrote his take on the Civil War, aptly called “The Rise and Fall of the Confederate Government.” Once defeated, he was arrested for treason but never convicted. Instead, the federal government took away his right to run for office. The right was eventually restored – in 1978.

Two years after his death, his widow, Varina, moved with their youngest daughter to New York City. How ironic. The widow of the man who led the revolt against the north taking refuge in the lap of northern capitalism and culture.

Biloxi has a history that is tied to water and to war. The Biloxi lighthouse, built the same year as Beauvoir, still collects visitors with a warm spot for nostalgia. Situated on the banks of the Mississippi Sound, the breezes of the Gulf Coast are only a short distance away. Separating the Mississippi Sound from the Gulf waters are islands with names such as Cat, Ship, Horn, and Petit. Not to forget Bois and Dauphin islands.

Oyster luggers and shrimp boats once dominated the waters off of Biloxi. These days the oysters are harvested with mechanical arms attached to the sides of boats; in the early days, it was men who were armed with hand rakes and tongs. Even in modern times, the language of an oyster lugger remains relatively unchanged.

Besides canneries and lighthouses, between the end of Jefferson Davis’ war and the Second World War, Biloxi became a vacation spot of sorts. Tourists and illegal money flowed to the Broadwater Beach Hotel and Resort, whose first owner was a rum runner along the coastal shores. With the end of Prohibition, the entrepreneurial hotel owner added illegal gambling to his list of southern hospitalities.

Army Air Corps Station Number 8, Aviation Mechanics School, Biloxi, Mississippi, opened for service on June 12, 1941. It would be officially designated as “Keesler Army Airfield” a few months later on the twenty-fifth of August. By the time it was finished, Keesler was the costliest federal project ever undertaken in the state of Mississippi.

The immediate arrival of recruits swelled the local jaunts. Watering holes and dance halls were filled with khaki shirts and cocky attitudes. The Kansas kid who’d rather be wearing overalls met the city boy courtesy of Biloxi, Mississippi. Within months, thousands of young men would descend on Keesler to learn the ways of war.

In a matter of months, the sleepy little coastal town of Biloxi, armed with the charm of Beauvoir and smelling like oysters, would be forever changed by the engines of war.

##########

Bobby Buchanan was typical of the boys signing up for the United States Army Air Force. Young, brash, gung-ho, a bit of a hot-head. He had, as many others before him, tried to enter the Army before he was old enough. A few of his friends had slipped in. Most of those had been sobered up about the realities of war within months of enlisting.

Buchanan was the oldest son of a welder and his wife from the Southside of Chicago. Shortly after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, Bob’s dad went from welding radiator coils to assembling the underbellies of planes that would fly in the European theater. His factory had been retrofitted to take large slabs of sheet metal and twist them into part of the fuselage. The war effort was demanding, often requiring twelve to sixteen hour days. Days no one complained about, at least out loud.

The Buchanan clan consisted of mom, dad, and three boys. Bob was the oldest by nearly ten years and sixteen inches. The two younger Buchanans, Albert and Ernie, were separated by five years and a few months. Each of them had fiery red hair, as did the postman. Or so the joke went.

Though technically a Catholic by birth, he was no altar boy and that was by choice. Every so often he bumped into Father Santini who would greet him with a “Robert Buchanan, I watched your poor grandmother die with your name on her lips. She died with a broken heart.” His head would twist sharply to the side, a grimace on his face. Then, as if shaking off cobwebs, he would shudder back and forth and continue on his way. Even the saints embedded into the cathedral’s concrete seemed to be staring down their holy noses at Robert Buchanan.

Growing up on the Southside during the late 1930’s was an everyday catechism

on survival. Bobby was more at home on a street corner, rolling dice and cigarettes, than he was on a wooden bench seemingly designed to pain one’s backside. He started smoking at age thirteen and was sneaking into his dad’s liquor cabinet by age fifteen. And he hung with guys who did the same and attracted young gals who wanted to.

He fathered his first child out of wedlock after his first weekend of binge drinking. He was a hair past his sixteenth birthday. She wasn’t a girlfriend, she was available. To tell the truth, he wasn’t quite sure of her name. Just when he thought he should “get to know her better,” her mother shipped her off to an aunt in Kansas. She never came back and Bob was fine with that.

Within a year he had fathered his second child. This was the result of his first long-term relationship, a courtship that had peeked and busted at about three and a half weeks. He tried to make it work. He worked at learning her name, trying little tricks he picked up from a nickel book he had bought at the store. “Find something that rhymes with the name you’re trying to remember.” Louetta. What rhymes with Louetta? What kind of evil, sadistic parent would name their daughter Louetta?

Finally he settled on “forgetta Louetta.”

Unfortunately for Bob, Louetta didn’t leave. No aunts lived outside the city limits of Chicago, except for one who strayed as far as Gary, Indiana. One month after finding out about her pregnancy, Bob’s Catholic guilt kicked in and he decided to ask her to marry him. She laughed, a wide gaping smile. And it was then that he realized how much her missing tooth really bothered him. And he laughed, too, laughing at his good fortune that she turned him down.

Many years later, Bob’s youngest brother Ernie would hire a young secretary with less than stellar teeth. The curve of her nose, the dipping of her eyebrows, several things about her facial features struck him as familiar. It wasn’t confusion with a movie star, far from it. And when Rondella Buchanan left a next-of-kin contact number, the name Louetta Jipswich meant nothing to him.

Robert Buchanan found himself sitting with an Army recruiter late on a Friday afternoon. The sergeant had correctly sized up this 145 pound potential recruit: Eighteen and anxious and drifting. A quick glance at the paperwork showed he was single and had no dependents, none on paper. In good health. GED. No arrests. Irish Catholic. A few strokes of the pen made it official – Robert Buchanan was joining the United States Army.

His father took a rare vacation day to help Bob gather his things. It would be the last few hours they would share together. The first Buchanan casualty claimed by the war would not be Robert Fay Buchanan but his father, victim to a splintered piece of scrap metal dislodged from a fabricator two tables away.

Three days after signing the papers Bob would be on his way, headed south. Headed to Biloxi.

##########

I felt as if the letters were shouting at me. CERTIFICATE OF DIVORCE. Rita didn’t as much hand me the paper as she let it fall, as if it were on fire. Free of the paper, she let her head resume a normal position, no visible damage to the wall or head.

“This is to certify the dissolution of marriage between Robert Fay Buchanan and

Pauline Sandifer Buchanan. Date of Marriage: September 5, 1943. Place of Marriage: Tabernacle Baptist Church, Biloxi, Mississippi. Date of Divorce: November 11, 1943. Cause of Divorce: Adultery. Signed: The Honorable Horace Smiley.”

Blinking a few times, I looked again but the words were the same. I danced my fingers lightly across the county seal. It felt real enough, a bit fuzzy but worn. Though her friends all called her Paulie, her given name had been Pauline Ann Sandifer. Pauline I knew. Pauline Sandifer I knew as well. Pauline Buchanan was a total stranger.

##########

We sat silently surrounded by shoes, mom’s shoes. Paulie Buchanan’s shoes. Since I was the last in, I was the first to leave, being careful not to tango with any red pumps. Rita followed looking like a defeated crab. Making our way to the kitchen table, I placed the unfolded piece of paper in the middle of the table and we both stared at it. Somehow staring at it might make it go away or make sense, and I was happy with either outcome.

“What do you think this means?” I asked. “I think it means they got divorced, you knucklehead.” Rita had long ago dubbed me Master of the Obvious and for good reason. Although I considered myself perceptive and aware; she called me retarded.

“I know that. But I never knew Ö”, my voice trailing off as I wondered what else I might not know about my parents. Were they on the run from the law? Had they killed anybody? Espionage? Bootlegging? Did mom have any tattoos? Before my mind could add the Technicolor to such wild thoughts, Rita chimed in with “I didn’t know either.” Her voice softer, devoid of teasing or sarcasm. Her words brought my eyes back into

focus.

Then, as if snapping out of a trance, Rita dashed from the table and went scrambling back into the closet. Shoes went flying. She emerged with the old floral box in her arms. It went down on the table with a thud, upside down, scattering all the contents within a two-foot radius. Every paper was unfolded, every envelope opened. Each and every picture was inspected as if it contained a hidden code.

There was nothing else, nothing that would shed light on the CERTIFICATE OF DIVORCE. No pictures we couldn’t place. No love letters or poems or Biloxi postmarks. Everything else in the faded box belonged to Pauline Ferguson, not Pauline Buchanan. The only place Robert Fay Buchanan existed was a single-spaced line, typed in an old Roman font on a yellowed piece of paper.

##########

Early fall, 1943.

Bobby Buchanan was one of the lucky ones. Yeah, right. After finishing his basic training at Keesler he had hoped to be assigned to a base on the west coast. Somewhere far away from Biloxi and Dixie flags and stickers that read, “Lee may have surrendered but I never did.” Heck, he nearly started a brawl by telling some drinking buddies to get over that Civil War thing. It was getting really old.

No sir. Others were packing their bags and heading for the train depot. He’d be in Biloxi for another three months, the victim of some aptitude test that indicated he was better at using his hands than his head. He wouldn’t fly the planes or even guide them. He would keep them greased. He’d waited two years to join the Army only to become a

grease monkey. Writing on the blank side of a Beauvoir postcard, Bob couldn’t bring himself to use the word “mechanic.” Back in Chicago, Father Santini would listen to a proud mother talking about her “aviation specialist” and try not to grimace.

Bob had helped his father deconstruct quite a few things: an old refrigerator, the transmission of an uncle’s Oldsmobile. Deconstructing was fun. It was like an afternoon romp with a girl whose name you should know but don’t and don’t care to learn. It was easy. Putting it back together, well, that was another story. It was becoming obvious that the U.S. Army expected him to put things back together.

The instructors at Keesler treated the technical manuals like classified documents, which, of course, they were. Few of the titles had less than seven or ten words. “A Guide for Inspecting and Repairing Motorized Panels in General Aviation Planes.” Inside were acronyms and initials. Abbreviations everywhere. Apparently the manuals were designed to confuse not only the enemy but also the men required to read them. Worse yet, he now found himself speaking in short-hand and he hated it.

Life at Keesler was far from fair. The fly boys had leather jackets and attitude; Bob had diagrams of bolt patterns and wiring schematics. The resentment only grew when the fly boys and grease monkeys ended up at the same bar, eyeing the same gals. How could a grease monkey compete with a pilot. Not just any pilot, a fighter pilot. “That must be soooo dangerous.” That would be all the opening a fly boy would need. “I’m prepared to die if my country asks me to.” Game over for the grease monkeys.

Not all girls required a dose of bravado; all some needed was a uniform. When the occasion called for it, Bob Buchanan became an “aviation specialist” and hinted at top-secret manuals that he’d like to talk about but couldn’t. Could get court marshaled

for that. “You might be a German spy, sweetie. But for those blue eyes I might be persuaded to change sides.” The girls would giggle; the other “aviation specialists” would roll their eyes (and try to memorize the same lines). You didn’t have to be original, just good.

The dance halls were only open on Friday and Saturday nights. In Chicago, night clubs were open every day of the week, including Sundays. Not in Biloxi. One of Bob’s fellow classmates, a corn-bred farm boy from Alabama said something about “blue laws.” Color-coded laws? Noticing the puzzled look on Bob’s face, he added, “we have to respect the Sabbath.” Bob had known a few Jewish dice players back on the Southside and they had never said anything about respecting the Sabbath. Still, he wasn’t sure what being Jewish had to do with closing dance halls on Sunday nights.

So he danced and drank on Friday and Saturday and respected the Sabbath on Sunday. Not that he was doing anything specific, or different for that matter. “I’m respecting the Sabbath” he would say to friends. “That’s funny, it looks to me like you’re playing dominoes.” Nonetheless, he made sure on his next postcard home that he let his mom know he was respecting the Sabbath. He didn’t expect her to get it either.

Duke Ellington was gaining popularity as jazz began to spread across the country. In January of 1943 he would play his first concert at New York’s Carnegie Hall. New York City, Chicago — they had jazz clubs. Biloxi had honky tonks. More than a dozen beer joints had sprung up within a mile or so of Keesler. Walking and stumbling distance. Each followed a basic formula: loud music, over-crowded dance floor, cheap beer, and girls. Girls who swooned over aviation specialists.

There weren’t enough gals from Biloxi to pack that many clubs. Skirts had been

imported from places like Mobile and closer spots such as Pascagoula and Pass Christian. For those who had come from smaller towns (like Corinth or Holly Springs), Biloxi was big, intoxicating, a bit scary at times. Those were the ones who smoked Pall Malls to both appear sophisticated and to calm their nerves. Most were in their late teens to early twenties, single and bent on not staying that way.

It was at the honky tonks that two competing missions collided — both involved pursuit but with varying levels of responsibility and commitment. Each raced against the same clock. For soldiers and recruits, the pursuit was about enjoying the company of a pretty girl while awaiting the next deployment. “Passing the time in my sweet baby’s arms.”

Two cottage industries nearly sprang up overnight, each siding up to a competing mission. Motels and drive-in theaters picked up where the honky tonk left off. The second industry to thrive was the county coffers that collected and deposited marriage license fees.

Girls from Biloxi could afford to be patient; a new batch of recruits arrived each week. It was the out-of-towners, especially those from small towns and poor families, who measured their odds by the amount of money left in their purse. Some had saved up enough, with a little help from a sympathetic aunt or uncle, to spend three earnest weeks in pursuit of a soldier. Three and a half weeks if they risked their Greyhound fare to stay a bit longer.

Robert Fay Buchanan knew how to navigate inside of a motel; he had no interest in marriage.