Description:

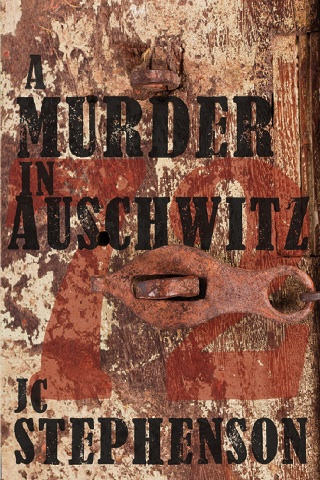

Manfred Meyer is forced to build a defence for him in his court martial. Drawing on his years of experience as a criminal lawyer in Berlin, Meyer must unravel the deceit and interpret the lies that infect the concentration camp and work to have him found not guilty.

Following Meyer and his family through their lives in Berlin, the Nazi rise to power and their inevitable arrest and incarceration in Auschwitz, Meyer will do almost anything to see his wife and children. Almost anything.

Can his abilities as a lawyer interpret the facts of this seemingly impossible case? As a Jew, should he even defend an SS officer? And is he actually guilty of this crime?

But the officer must be found innocent if Meyer is to see his family again.

This story follows Manfred Meyer, from his beginnings as a lawyer in 1930s Berlin after being taken under the wing of the city’s most capable defence lawyer in the most prestigious law firm in Germany, Bauer & Bauer.

Meyer’s confidence and experience build as his cases become more complex and more difficult to defend. His success is widespread and he, his wife Klara and their twin daughters live a comfortable life in the capital.

But Germany is changing. The Nazi Party has come to power and Meyer’s Jewish heritage has become a crime. Life becomes more and more difficult until even in spite of Meyer’s connections he is forced to leave his position as Bauer & Bauer’s pre-eminent lawyer.

Then, one night, the inevitable knock at the door heralds the long train journey to the east and the death camps of Poland for Meyer, his wife and his children.

Split from his family on arrival, Meyer does what he can to survive in a place designed for death. He stays alive with help from the other inmates he has befriended, helping each other through the long days of hard labour, his only wish being that he could see his family again. A forlorn hope until circumstance throws a real chance his way.

Book Rated: G

e x c e r p t

[Web-Dorado_Zoom]

Auschwitz, 24th July 1943

MANFRED Meyer stood in line. His eyes darted from left to right as he tried to take in as much about this place as possible without standing out. Or perhaps it was fear that kept him facing straight ahead.

He did not know where he was, but he had caught a glimpse of an old railway sign from the tiny crack in the cattle truck door that he had been forced up against for most of his long journey. It had read Oświęcim. This must be Poland.

Where were his wife and daughters? Meyer’s stomach ached at the thought of them.

His eyes searched the area. Meyer turned his head slowly and tried to see behind him, but all that he could see was a mirror if what lay ahead of him; a never-ending line of men. And soldiers.

There had been brandished guns, shouted commands and pushing and pulling when they had first arrived. This had been some kind of selection process; old from young, men from women.

And then a quick march to this point. The soldiers were quiet now apart from the occasional shared joke, waiting for something.

Now Manfred Meyer waited too. With all the other men, some young, some middle-aged, some much older than Meyer. But no-one very old and no children.

Where were his children? Were they standing in a line like he was? They would still be with his wife – hopefully. At least they would be together so they wouldn’t be too frightened. His stomach turned over again at the thought of them being afraid.

It was hot. And this place stank. It was a smell he had never experienced before. It had penetrated the train even before it had stopped. The stench had overpowered the dreadful smell of sweat and urine and defecation which had filled his carriage. It was much worse.

It was a mixture of all the unpleasant, unclean, unwanted smells in the world. It was a thick loathsome odour. It sat on your tongue and forced you to taste the pollution. And there was something else. Something sweet. Meyer couldn’t put his finger on what it was but it repelled him.

Meyer’s thirst taunted him. He watched a bead of sweat slowly trickle from the hairline of the man in front. It caught on a black hair on the back of the man’s neck and hung there like dew on a blade of clean, cold grass.

Then there was a shout. Orders being conveyed from one soldier to another from the front of the line. In spite of the shouts, the line of men did not move. He tried to see what was happening but it was out of sight. He stole a glance at the two SS guards nearby.

Summer clung to the battle helmets and jackboots they wore. They carried their rifles in their hands, not slung over their shoulders, and stood in their dusty field grey uniforms with full webbing as if waiting on an attack from a crack Red Army brigade. For a moment Meyer wondered if they were perhaps afraid of the huge number of men they had in the line. If everyone charged the guards they could easily overpower them.

He tried to look down the line again but his attention was taken by the drop of sweat on the back of the man in front’s neck. It still sat on the hair. It vibrated from the heartbeat of its owner as gravity attempted to drag it to its inevitable end. Meyer watched it bulge into a teardrop and then back again to its rounded shape and although it moved infinitesimally closer to the end of the hair, it still clung on for dear life.

There was further shouting and then someone up ahead was pulled from the queue. In spite of the distance, Meyer could make out that he was wearing very smart clothes, a grey suit and a flash of a white collar. The man was gesticulating at a guard and an officer. Meyer strained to hear what was being said, but the man’s voice was carried away on a sudden breeze. Dust was blown around them all and a speck got into Meyer’s eye. Instinctively, he turned away from the direction of the wind and through his watery vision saw that his SS guards had been caught unaware by this sudden flurry of granular dirt. Together, both guards and prisoners suffered from this irritation.

Once Meyer had rubbed the dirt from his eyes he once again caught sight of the smartly-dressed man, now on his knees and holding his hands together, pleading for something. But Meyer still couldn’t hear.

The officer put his hand on the guard’s shoulder and said something that was taken away on the wind, then walked around to behind the smartly dressed man and took out his pistol. The guard moved away, pointing his machine gun at the man.

The smartly-dressed man stopped talking and his arms dropped to his side. His head bowed forward and he sat back on his legs. He looked like his life had left him already.

Meyer closed his gritty eyes and waited for the noise. He could hear the dust-filled breeze pass over his ears and he could hear the voices of soldiers talking. And then he heard the crack of the gunshot.

Meyer opened his eyes and saw that the officer had already holstered his pistol and was walking away. The smartly-dressed man lay face down in the dirt. A dark pool surrounded his head. Thank God his wife and children had not had to witness this.

Maybe family units would be re-united once they had been processed. He had heard the use of this word several times since arriving. There would be a processing of prisoners, or that there was a processing procedure.

Meyer’s attention was once again taken by the back of the man’s neck. The drop of sweat had gone.

Now there was more shouting. Meyer hoped it wasn’t going to be another execution. He looked desperately up the line of men, but instead of a victim being pulled from the queue, the guards were gesturing to everyone to start moving forward.

Meyer’s two SS guards walked slowly closer to the line, keeping a watch along the queue, waiting for the forward movement of the prisoners to snake backwards to their position. Both of these men were young, no more than twenty-two years old and although they were both clean-shaven, the dirt and grime of the heat stuck to their faces like a beard.

Meyer watched with them, waiting for the man in front to step forward. He wanted to make sure that he was moving as soon as possible, not giving the guards any reason to single him out.

Then, to Meyer’s horror, the sweaty man in front collapsed. He fell straight down as if his legs had disappeared completely, until he was sitting in the dirt. Then he toppled over sideways.

Meyer stopped breathing. The line of men in front had started to walk away. He didn’t know if he should step over the collapsed man, or bend down and help him or stay where he was until the guards removed him.

Meyer looked to the two SS guards for guidance.

“MOVE!” screamed the closest guard. A tiny particle of spittle left his lips and landed on Meyer’s face. His comrade joined in the command before Meyer had had a chance to step over the collapsed man.

“MOVE!” came the command again, and the guard’s hand shot out to grab hold of Meyer’s arm.

He felt himself being pulled forward over the sweaty man’s body. He stumbled, and for a second he thought he was going to join the other man face down in the dirt, but he managed to keep his feet and, with the guard now shouting at the men behind him, Meyer walked quickly to catch up with the rest of the queue.

He snatched a look back and saw that the line of men was being forced to walk over the collapsed man’s body. It wouldn’t be long before he died, if he wasn’t dead already.

Meyer considered that in the past few minutes two men had lost their lives. He hoped that this wouldn’t be a pattern for the rest of his time here, before he was processed.

Berlin, 14th November 1929

MANFRED Meyer sat on a green leather bench in the cool,

walnut-panelled hallway of the Bauer & Bauer Criminal Lawyers office on Potsdamer Platz. A trickle of sweat ran down his back in spite of the temperature.

He wore his whitest shirt with a dark tie, his good suit and shoes, and, after much deliberation, had his coat folded over his arm.

Meyer couldn’t get comfortable. He crossed his legs and sat back. Then uncrossed his legs and leaned forward. He stood up. Walked down the hall a short distance and examined one of the portraits hanging there.

It was of an elderly gentleman in a black suit with snow-white hair and a kind face with a ruddy complexion. He was seated in an office which was wood-panelled, not unlike the hallway where Meyer now stood. The oil paint had stained over the years, and Meyer felt the urge to run a wet finger over the painting to bring up the original colours.

“Herr Meyer?”

The voice startled Meyer from his examination of the picture. He turned and saw a tall, middle-aged man half hidden by the doorway next to the bench he had been sitting on.

“Yes. Yes, I am Herr Meyer,” he replied and started to make his way towards the man.

The man stood to one side and indicated with his arm that Meyer should enter the room.

“Please come in, Herr Meyer, and take a seat. Herr Bauer will see you forthwith.”

Meyer followed the man’s instructions and entered a windowless,

high-ceilinged room with a large door on the back wall and another, slightly smaller, door behind a beautifully carved desk. He looked around but could not see a chair.

The man followed Meyer in and shut the door behind him.

“I am Herr Muller, Herr Bauer’s secretary,” he said as he took his seat behind the ornate desk. Muller then noticed that Meyer was still standing.

“Please, Herr Meyer, sit. Herr Bauer will be with you soon,” and indicated with his hand a small wooden chair which Meyer had not noticed as it had been behind the open door.

“Thank you,” replied Meyer, and sat down.

Meyer decided that he should not go through the dance he performed on the bench outside and chose to sit with his legs together and his coat folded over his arms, resting on his knees.

Meyer surveyed the room while Muller occupied himself with writing at the desk and occasionally stamping and moving paper from one pile to another. There were more portraits on the cream walls as well as a mahogany clock and two different sized metal filing cabinets in one corner.

Occasionally, Muller would look up from his writing desk at Meyer, stroke his moustache and then continue with his work.

After a few minutes the large door on the back wall opened and an amiable looking gentleman filled the doorframe.

“Herr Meyer,” his voiced boomed. “How very pleasant to meet you.”

Manfred Meyer stood up and walked over to shake the man’s hand.

“Friedrich Bauer,” he announced, and took Meyer’s hand in a great paw. “Please come in.”

Meyer followed Bauer into his office. It was opulent. Beautiful paintings hung on every wood-panelled wall, and the ceiling had deep, moulded cornices and an enormous rose, from which a chandelier hung, its electric lights sparkling in the crystals. In the centre of the room, an Indian carpet covered most of the dark floorboards on which sat a desk that was even larger and more ornate than Muller’s. So large in fact, that a telephone, various ornaments, piles of papers and books, a crystal water jug with glasses, an ashtray and an inkwell with pens which sat around the perimeter of the leather insert still left vast amounts of space available for work.

Bauer made his way around the desk to take his place on the leather wing chair and indicated to Meyer to take a seat opposite on one of the much smaller but just as beautiful guest chairs.

The large man held a handkerchief to his mouth, coughed, and cleared his throat.

“Damn cough,” he apologised. “Can’t seem to shift it. Now Herr Meyer,” he continued, putting his handkerchief back in his pocket. “I have heard some very good things about you.”

Meyer smiled. He had sat as carefully as he had done in Muller’s office; legs together, his coat folded over his arms and sitting on his knees. Meyer thought that this seemed the most respectful and attentive way to sit. Then he thought that he might be thinking too hard about his posture and not concentrating on the reason that he was in this office.

“Why don’t you tell me a bit about yourself?” asked Bauer.

Meyer took a deep breath. This was it; his only chance.

“Herr Bauer, first of all I would like to thank you greatly for allowing me this opportunity to see you and state my case for engaging in full employment with Bauer & Bauer. As I am sure you are aware, as you are in full possession of the facts of my visit to you today, let me please start by telling you about my personal position before moving on to my professional qualifications, experience, and requirements.”

Meyer noticed that Bauer’s eyebrows rose almost imperceptibly and that he sat slightly forward in the wing chair. He was surprised and interested. Meyer realised that he had hit the correct note.

“I live with my wife on Zehlendorf Strasse in an apartment overlooking the market. We have been married for a year and a month and she is expecting our first baby.

“We moved to Berlin from Leipzig ten days ago with the express intention of myself gaining employment in a criminal defence lawyer firm, Bauer & Bauer being my preferred option.

“I took my law exams at Leipzig University and have been an intern at Schubert’s Law Office for the past two years. I believe that Herr Schubert and yourself are well-acquainted. He has spoken very highly about Bauer & Bauer and encouraged me to seek employment with you.”

Bauer gave a smile which showed nicotine stained teeth with a pipe hollow.

“Yes, Franz Schubert and I are very well-acquainted. We passed through law school together.” He then chuckled and leaned even further forward in his chair and whispered, “There was the possibility of neither of us graduating. A story I may tell you some other time.” He leaned back in his wing chair and felt around in his pocket. Bauer produced a pipe and waved it at Meyer. “Do carry on Herr Meyer. Don’t mind me if I smoke.”

“Yes, Herr Bauer. So I discussed this possibility with my wife and explained how I felt that Berlin would offer many more opportunities for a prospective criminal lawyer than Leipzig might.”

Meyer watched as Bauer continued to fish around in his pockets until a pouch of tobacco was found.

“And if Frau Meyer had not wished to move to Berlin? After all, she must have been heavily pregnant?” he asked, while now searching the table for something.

“Then I would have persuaded her, Herr Bauer,” replied Meyer.

He spotted what Bauer was looking for and leaned forward to pick up a brass pipe lighter and passed it to the large, grateful hand of the old man.

There was a twinkle in Bauer’s eyes.

“Persuade her? Do you think that would have been possible? Women, especially spouses, are so very difficult to persuade, don’t you think?”

“Herr Bauer, my wife is the most intelligent woman I have ever had the pleasure of knowing. I would not attempt to convince her of anything unless I truly believed it to be the case.”

Bauer had tucked some tobacco into his pipe and was sucking the flame from his lighter into the bowl while puffing out smoke from the side of his mouth.

“And if Frau Meyer wanted a new pair of shoes, do you think you could persuade her otherwise?”

Meyer thought for a moment before replying.

“If my wife required a new pair of shoes, I would not wish to dissuade her from the purchase.”

The old man smiled but continued his questions.

“Ah yes, but if there was no requirement. If it was a desire, would you be able to bring your powers of persuasion, such an important skill in a lawyer, could you bring your persuasive powers to the fore and convince her that she does not require the shoes?”

Again Meyer paused before answering.

“Herr Bauer, as she is my wife and I have promised to give her all she requires and desires in our life together, I would never attempt to dissuade her from such an inconsequential purchase or convince her otherwise. However, I am certain that I could persuade any other woman in Berlin that a purchase of unrequired shoes would be entirely unnecessary due to any number of factors which would include fashion, sensibility due to the time of year and possible poor quality of the product. But my main argument would be that I had seen such a pair of shoes on one of her friends.”

Bauer smiled. He waved his pipe around before clamping it between his teeth and asking Meyer to continue.

Meyer paused. He realised that he had lost his train of thought. He had tried to give his case to Bauer as if in a court of law and, mid-way, this amiable old man had broken his concentration through a series of questions about shoes and the search for a lighter for his pipe.

“Do carry on Herr Meyer, please,” he said, while producing larger and larger amounts of smoke.

Meyer stumbled for words as he tried to pick up from where he had been interrupted.

The old man took the pipe from his mouth and gave Meyer a wide smile and scratched the yellowed whiskers around his mouth.

“Herr Meyer, you certainly talk like a lawyer. But…,” he trailed off and stared into the bowl of his pipe before letting his eyes rest back on Meyer again.

“But your train of thought was broken quite easily by the use of some very simple courtroom techniques. The distraction of the finding and lighting of the pipe while I moved the questions away from your main theme but included some of your own elements so that you wouldn’t notice me make your train jump the tracks. I then continued down my own track, taking you with me until your train became derailed completely.”

Meyer felt his stomach turn over. He had blown it. He had practised his resume in his own mind so often, along with how he would be able to prove his worth to this firm.

Bauer continued. “And this is something you only learn through experience. You were able to formulate an argument about a subject and discuss it and answer questions until you found a final solution which satisfied me.

“My old friend Franz Schubert also telephoned me to tell me that I was to look after you and give you a job. Even if it was to deliver the mail. But after meeting you and having our little game this afternoon, I can see that you will make a very able lawyer one day.

“This is Thursday, which will give you three precious days to spend with your expectant wife before you start work here at 8.30 precisely on Monday morning.”

Meyer jumped from his seat. “Herr Bauer, thank you. Thank you very much for this opportunity.”

The old man stood up, put his lit pipe in his pocket, and held out his great paw of a hand, which Meyer took and vigorously shook while nervously glancing at Bauer’s smouldering jacket.

“Herr Meyer, wear the suit you’re wearing today and visit Herr Muller first thing. You will be working with Herr Deschler, who requires an assistant.”

Meyer had heard of Deschler. He had been reading in the papers about an ongoing murder trial he was involved in. It was occasionally making front pages. Meyer thanked Bauer again, turned, and left through Muller’s office, politely bidding him goodbye. He forced himself not to break into a run as he walked down the walnut hall. Meyer couldn’t wait to tell his wife Klara the good news, and a smile spread across his face as he descended the grand staircase and left the building into the winter sun shining down on Potsdamer Platz.

Under different circumstances, he would have walked home in the low afternoon sun, but he wanted to tell his wife the good news as soon as possible.

He found a tram stop and scanned the timetable for the tram which passed close to Zehlendorf Strasse. The 14A took him to within two or three minutes of his apartment and, after checking his wrist watch, he saw that is was due in seven minutes.

Manfred Meyer checked his pockets for change and found the twenty pfennigs he would need for the journey. He checked his watch again and was dismayed to see that it was still seven minutes until the next tram.

He thought about how happy Klara would be when he told her the news that he would have a real paying job with an excellent law firm and fantastic opportunities for his, her, and the soon-to-be-born baby’s future. He realised he hadn’t even asked about money when he was with Herr Bauer. No matter, as long as there was enough to pay their rent and look after his wife and baby, that would be all he would need.

He watched as a green tram turned into Potsdamer Platz, sparks showering from the overhead wires, wheels squeaking on the steel rails. This terrifying dragon was going to be taking him home. He climbed aboard, took a seat, and paid the conductor his fare.

Twenty minutes later Manfred Meyer stepped from the creaking old bone-shaker and made his way down Zehlendorf Strasse towards his apartment at a quick march. He smiled at the paper seller outside the stair door to his apartment, the newspapers still full of news of the great crash on Wall Street in America but also about the upcoming Berlin Municipal Elections. There were election posters from all the various parties all over the city. On a bill poster bollard next to the paper seller, some new posters had been recently added by the German National People’s Party, the Communists, and the National Socialist Workers Party, all advocating change and smashing corruption.

Meyer used his key in the main door and ran up the stairs to the second floor, clinging on to the ornate bannister as he went. He found his apartment door ajar.

“Klara?” he shouted through the door, before pushing it fully open. Inside, he was greeted by a middle-aged woman that he had never seen before, wearing a white full length apron.

“Herr Meyer?” she asked.

“Yes, where is Klara? Is everything alright?”

Meyer tried to look beyond the woman, whose full figure barred his entrance into the apartment.

“Herr Meyer, please calm down. Everything is as it should be. I am Birgit Dietrich, and I am a midwife at the Berlin Charite Hospital. I am a friend of your neighbour, Frau Fischer, and luck would have it that I was visiting her.”

Frau Dietrich gave a huge smile.

“Herr Meyer, congratulations. You have two beautiful, healthy baby girls.”

Meyer could feel tears of joy prick his eyes. He could see into their bedroom but only the bottom of the bed was visible. Someone was moving around in the room.

The midwife followed his gaze. “Frau Fischer is just cleaning up. She is a retired nurse herself, of course, and you should be able to see your wife and babies in a few moments. Please wait here,” she said firmly as she returned to the bedroom.

Meyer stood frozen to the spot. He could hear low voices in the room and then a tiny cry; a scrap of life making itself heard in the world.

“My God,” he whispered to himself. “Twins.”

Auschwitz, 24th July 1943

MEYER was conscious of keeping his feet as the line of men marched under a gate that shouted ‘Arbeit Macht Frei’ – ‘Work Will Make You Free’. This must be some kind of hard labour camp.

He could see what looked like barracks up ahead, as well as guard towers and sentry boxes. They were kept marching until the full line of men had snaked through the gates. Then the command to halt was barked out by the guards.

It was very quiet considering the number of prisoners and guards that were there. Then he heard what, at first, sounded like birdsong but turned out to be the squeak of a wheel-barrow being slowly pushed by a short, thin man wearing a striped uniform. He looked as if the colour had been entirely removed from his face and clothes, only leaving different shades of grey.

The man’s eyes bulged from his sunken cheeks and, for a split-second, his eyes met with Meyer’s as he passed. Meyer could see something in that gaze. He had seen it before in the courtroom; it was when someone was found guilty. No matter how petty or extreme the crime, that moment of being told that you were guilty and would be punished was difficult for everyone to bear, even if that moment was fleeting.

The man looked guilty and frightened, but the look was unfocused, almost dead. And what else did Meyer see in those eyes? Was that pity?

The wheelbarrow man passed by, followed at his shoulder by another thin, grey-striped man who looked almost identical, although slightly taller. Both were escorted by a guard with a rifle over his shoulder.

The smell was worse now. Perhaps the men who had passed him also carried the odour on them. It may have insidiously infiltrated their very being, breathing in the stench every day until it escaped from their pores. And then that sweet tang in the air. It sent a shiver down his spine even in the heat of the sun.

Meyer’s tongue was dry. He hadn’t been this thirsty for a long time. How long would they have them stand in the heat of the day before allowing them shade and something to drink?

He hoped Klara and the girls were not stood in the heat like this and that they had been looked after a bit better than the men. He was sure that even the Nazis would discriminate between how men were treated and how women and children were looked after.

Meyer watched as the guards quenched their thirsts from their water canteens. When would they give them water? He felt the grey dust from the camp stick to his face and clothes and wondered if this was sucking the colour from him, leaving him like the men with the wheelbarrow.

Soon he heard the false birdsong of the barrow approaching from behind. As it passed, he could see the two striped men now holding a handle each, struggling to push it over the baked, hard dirt, and the arms and legs of the two dead men from outside the gates hanging over the rim of the barrow.

A few moments later there were further shouts, and the line of men began to move again. This time it was a faltering walk forward. Meyer could now see that they were being taken slowly into a wooden hut.

As soon as he was inside, instructions were barked at the men to undress. There were more of the striped men inside, who were gathering up the clothes being discarded on the floor and taking them out of a side door.

Meyer removed his clothes and shoes as quickly as possible and dropped them on the floor next to one of the striped men.

The striped man tapped his own hand and wrist and indicated towards Meyer’s watch and fingers. His wedding ring and his precious watch. At first, Meyer thought that the man wanted them for himself, but then he realised that everything was being removed; rings, necklaces and watches. Meyer pulled off his wedding ring and, feeling his stomach lurch at losing this symbol of his love for Klara, dropped it onto his pile of clothes.

“Your watch,” said the striped man, his voice like sandpaper, and tapped his wrist again.

Meyer unbuckled the watch and turned it over one last time to read the back, ‘For all eternity, Klara’, before letting it slip from his fingers on to the pile of clothes that, until a few seconds ago, had belonged to him.

One of the SS officers who was shouting commands saw that Meyer was now naked and whipped him with a stick.

“Out the back! Quick! Move!”

Meyer pushed past those who were still undressing, back out into the hot sun. He did what he could to hide his modesty, but outside were more shouting guards and a buzzing noise which sounded like a huge insect.

There were rows of chairs which looked like the metal-framed and wooden-backed type that he had sat at in school. Above them ran a wire, from which hung large electric shavers. Naked men were being pushed into seats, their heads shaved before being pushed off again and ordered towards another hut.

Meyer stood for almost thirty seconds before being pulled by his arm and pushed into a chair by a striped man. His head was pulled to the side, then forward, then the other side, as the buzzing roared in his ears and raced over his scalp.

Before he knew it, he was pulled to his feet and pushed away from the chairs. Guards were barking orders at their newly shorn visitors.

“Move! Quicker! Through that door!”

Meyer could hear something from inside the concrete building he was being herded towards. He couldn’t quite make it out through the incessant buzzing of the razors and the shouting. It sounded like gas or air escaping from a pipe.

“Inside quickly!”

The press of the naked men took Meyer in through the door of the building. The sound was water. There were shower heads in the ceiling, spraying out water mixed with disinfectant. The flow of men took Meyer out of a rear door to the shower, back into the sunlight, where there was a line of trestle tables. The striped men were also here, directing the wet, naked prisoners to one table or another.

Meyer was directed from one striped man to another until he was finally directed to a table where an SS officer sat. The officer sat with a lined book in front of him and held a beautifully ornate fountain pen in his hand. Without looking up, he started asking questions.

“Name?”

“Manfred Meyer.”

“Date of birth?”

“8th of August 1905.”

“Place of birth?”

“Leipzig.”

Meyer watched as the columns were filled out in the register book.

“Profession?”

“Criminal lawyer.”

“Religion?”

“Atheist.”

The officer looked up at him and sighed.

“Religion at birth?”

“My father was Jewish.”

The officer wrote ‘Jude’ in his book.

The officer then turned to an assistant and stated, “Prisoner number 414894, Jew.”

The assistant dropped a folded set of striped clothes onto the table along with some wooden clogs. The officer pushed these towards Meyer and shouted, “Next!”

Meyer quickly picked up the clothes and turned away from the table. He could see others with their clothes going into a brick building that looked like a barracks, and decided to follow the crowd.

Once inside, Meyer watched the almost silent scramble to get dressed as quickly as possible. Nobody spoke. The only sound was the rustling of clothes and the sound of the wooden clogs as the men left the building.

He examined the bundle he had been given and began to get dressed. He had striped blue and grey trousers which he quickly put on, a grey-white vest, a blue and grey striped jacket which had a sewn patch with the serial number ‘414894’ and a yellow triangle over a red triangle forming a Star of David, and a matching striped hat, all of which seemed to be clean and perhaps even new. All except the clogs, which had obviously already had more than one owner.

As soon as he was dressed, Meyer followed the crowd through the door at the rear of the building and back into the warm summer day.

He found himself in a square where a knot of SS officer’s smoked cigarettes and laughed at each other’s stories. Guards with rifles slung over their shoulders pushed and shouted at the prisoners as they arrived in the square, organising them into ranks.

Meyer found himself in the fifth rank from the front, sandwiched between two men also marked with the Star of David. They both had the haunted look that the wheelbarrow men had shown. Meyer wondered if his eyes betrayed the fear and uncertainty that he felt.

The seemingly never-ending line of prisoners kept coming, until finally, the last man left the building, the door was shut behind him, and he was ushered into his position in the rear rank. But instead of something happening, the SS officers walked from the square leaving the men standing in the sun again.

The man to his left whispered something that Meyer couldn’t make out. He whispered again, this time loud enough for Meyer to hear.

“What is your name?”

Meyer whispered back his name.

“Itzhak Frank,” came an unrequested reply.

“Do you know what they did with the women?” whispered Meyer.

“I’m not sure. All I need is a drink of water.”

Meyer and the men stood for another thirty minutes before the SS officers returned, this time with clipboards, and started shouting out names which required a reply of ‘present’. Every single name that was called received an answer.

Once that exercise was complete, the name-checking started again, this time by a different officer. All names called out this time were to leave the ranks and line up next to an existing prisoner that the officer called a ‘kapo’.

Once a certain number of prisoners had left the ranks, the kapo led them away with the aid of a guard. Another kapo then took his place and the roll of names continued. Meyer was in the third group called out.

“Good luck,” whispered Itzhak Frank.

“You too,” replied Meyer.

He made his way quickly to the front and lined up with the others who had been called out. The kapo was a large man, thin but with obvious strength in his muscles, although he walked with a pronounced limp. His drawn cheeks betrayed a lack of teeth, while the scars on his face and a flat nose, broken at least once, were evidence of a violent past. Around his arm was a black band decorated with the word ‘KAPO’, while on his jacket, next to his prison number, he had an inverted green triangle.

There was a break in the calling of names and Meyer’s kapo nodded to the officer, turned, and led Meyer and the other men away from the square.

They were led silently to outside another brick building and told to line up. The kapo then produced a folded piece of paper and started another roll call. An armed guard stood several metres behind the tall man, his rifle hung over his left shoulder. This time, Meyer counted the names. Twenty-seven, including his own name, were called out. The kapo seemed pleased that there was no-one missing from his list and nodded to himself.

“I am Kapo Langer. You call me ‘kapo’, ‘sir’, or ‘Herr Langer’,” he started. “You will be in my hut and I am your leader. You tell me everything that is happening. You do as I say. I am the law in the hut. I am God.

“You can see from my uniform that I wear the green triangle. This means that I am here because I have been through the court system. Not because I am a queer, a communist, or a Jew. It is because I killed a policeman in a robbery.

“Even though you are Jews, you have all been born in Germany. That gives you certain privileges. The first one is that you will not be tattooed with your prisoner number. But you will have your photograph taken.

“You are lucky enough to have survived the selection process and have been chosen to work in the labour camp. Although, some would say that the others are the lucky ones.

“Welcome to Auschwitz.”

Berlin, 18th November 1929

KLARA Meyer kissed the back of her husband’s neck as he slept. It was Monday, and today was Manfred’s first day at his new job. She was so happy, a lovely new apartment, a new start for Manfred, and, best of all, two new babies.

She turned over and checked in the cot next to the bed. Both Anna and Greta were fast asleep, tucked up in a soft lamb’s wool blanket with little crochet hats and gloves on to protect them from the cold.

Klara looked over at the fire where she could see the glowing coals from the night before still keeping the worst of the chill from the room. It was pitch black outside but Klara kept a nightlight so she could look after and feed the babies. She checked the clock; it was 5.15am. Another fifteen minutes before the babies would need to be fed again. She looked forward to feeding them so much that she had to stop herself waking them early.

She felt Manfred stir behind her.

“Good morning, darling,” he whispered.

She smiled at him and stroked his face. She wished that he could spend more time with her and the twins, but if things went well at Bauer & Bauer for Manfred, it would give the family a fantastic start.

Her husband had been very considerate since the births on Thursday afternoon. She had hardly had to move as he fussed around her, making sure she had plenty to eat and drink or checking to see if she was comfortable. The previous night, he had even made sure that Klara had bread and cheese and an apple sitting ready for her breakfast on the table, covered with a cloth. The time that the four of them had spent together over the past few days had been very special.

He stayed in bed until the twins needed feeding again and then got up and added some kindling and more coal to the fire to warm the room for Klara and the girls. Then he washed, dressed, and had some bread, cheese, and coffee for breakfast. He kissed his wife and babies and, after protracted wishes of good luck, left the apartment for the journey to his new position, as an assistant lawyer in the office of a criminal law firm.

Manfred Meyer’s journey to Bauer & Bauer took almost exactly an hour, leaving him thirty minutes early. It was a cold, dry morning, and the darkness was being chased away by the emerging sun, making Berlin look like a watercolour. Meyer attempted to assuage his nervousness by watching people pass by on the busy street.

At 8:15 exactly, the great Black Forest oak double doors that guarded the entrance to Bauer & Bauer were unlocked from the inside by an unseen hand, and one of the doors opened to allow entrance to employees. Within a few moments, men in expensive suits began to disappear into the building.

Meyer waited until 8:20, took a deep breath, and headed in after them, up the marble steps and through the internal glass doors. His hands slid easily over the bannister of the grand staircase as he climbed to the top floor, where the walnut hall and Muller’s office was situated.

He expected to have to sit and wait for Muller to arrive as he hadn’t seen him pass through the door in front of him. However, the secretary’s office door was already open, and he was sitting behind his desk.

Meyer knocked on the door frame and bid him good morning. Muller checked his pocket watch and peered over his glasses at him before smiling.

“Good morning, Herr Meyer. Herr Bauer informs me that you will be working with Herr Deschler as his assistant. I am to take you to his office this morning. If you give me a moment to collect the mail which is to be posted, I will take you down to the first floor.”

Muller collected several envelopes from his desk, checking each one in turn, and then instructed Meyer to follow him. As they walked briskly along the walnut hall, Muller gave Meyer a quick history of Deschler’s time at the company.

“Herr Deschler started with us in 1920. He had been a practising lawyer for two years before volunteering for the front. He earned an Iron Cross before being badly wounded in the Somme, and then a British shell took his leg at Arras, after which he spent a year in hospital.”

Muller stopped at an open office door and took some envelopes from a wire tray before continuing with Deschler’s history.

“It took him another two years before Herr Bauer senior brought him into the firm.

“Herr Deschler is an excellent lawyer. He started, as all of our court lawyers do, with a relatively simple defence case, which he won. And then proved himself again and again. You will learn a lot from Herr Deschler. Only Herr Bauer has a successful defence record more impressive than Herr Deschler.”

They had stopped outside an office door, and Muller gave a quick two knocks before entering. Inside was an ante-room, slightly smaller than, and not as ornate as Muller’s. A young woman sat, working at a typewriter. She looked up and greeted Muller without missing a key. Muller nodded to her and proceeded to knock on what Meyer assumed was Deschler’s office door.

A simple “Enter,” came from inside.

Muller led Meyer into the office. Kurt Deschler had a glass of water in his right hand and a cigarette in the other. He had been standing, looking out of his window when the two men had entered his room. Meyer spotted a glass bottle, obviously medical in style, on his desk next to a jug of water. A walking stick was leaning against the desk not too far from the reach of the man. Deschler downed his glass of water and then, with a single limp towards his desk, opened a drawer and dropped the bottle out of sight without looking at it.

“Herr Deschler, this is Herr Meyer.”

“Ah yes. My new assistant,” said Deschler rather dryly as he held out his hand. Meyer stepped forward and shook it.

Deschler was around forty years old and slightly taller than Meyer’s one metre seventy. He had a full head of hair which had obviously been jet black when he was younger but now had silver streaks running through it, especially at the temples. He sported a similar style of moustache to Muller’s which contained a considerably higher proportion of grey than his head. Glasses sat on a thin nose, behind which an old scar ran over his left eye.

“Please sit down, Herr Meyer.” The tone of Deschler’s voice barely changed. Muller had already left the office as Meyer sat in a chair at the side of the room.

Deschler took a long drag on his cigarette and then put it out in a crystal ashtray on his desk, carefully folding over the end of the butt to ensure that the glowing tobacco embers were extinguished. The sunlight, now streaming in through the window, caught the long, slow plume of thin smoke that he blew across the room.

“So, Herr Meyer, have you assisted in a court of law before?” The question sounded more like a challenge.

“Yes Herr Deschler, I was an intern for…” but he was not allowed to finish.

“Good. You will know what to expect then,” came the interruption, as Deschler reached for his stick, took his coat off the stand and hung it over his arm. “We are in court this morning at eleven am precisely, court number three. The final day of my defence of a Gypsy in a murder trial. I am sure you have read all about it in the papers?”

Meyer had indeed been reading about this case.

“Yes, Herr Deschler. This is the trial of Prala Weide, the suspect in the murder of an elderly couple for the sake of a few Reichsmarks.”

“That is correct, Herr Meyer. And do you think he is guilty?” asked Deschler, as he pointed at two briefcases which he obviously meant Meyer to carry.

“I am not sure, Herr Deschler, but I would think that from what I have read, his innocence will be difficult to prove,” replied Meyer, as he picked up the cases and began to follow Deschler out of the room. He immediately realised the naivety of his answer when Deschler came to a sudden halt and turned to him.

“The first two lessons you need to learn, Herr Meyer, are these; first of all, unless they wish you to view them otherwise, which is very uncommon, your client is always innocent in your eyes. As you are my assistant, he is also your client. Secondly, and more importantly, you do not need to prove a man’s innocence, only his lack of guilt.”

Meyer noticed that Deschler’s eye, which carried the scar, was twitching. He wondered if this was a nervous twitch brought on by the final day of a trial, or caused by anger over Meyer’s schoolboy response.

“Today, I have to secure the doubt about Herr Weide’s guilt which I have been attempting to place in the minds of the jurors over the past week,” continued Deschler.

“I have to make sure that the doubt I have sewn is enough to overcome human nature’s requirement to find a reason for something happening. Each of the jurors we face today wants a guilty man to be provided to them to revenge the murders of that couple. As defence lawyers, this is the most difficult thing we have to overcome; not just to prove the lack of guilt of our client but to not then hand over a further suspect for them to inflict judgement upon. The perfect way to ‘prove a man’s innocence’ is to provide a guilty man in his place.”

Deschler turned, and, leaning heavily on his stick, led Meyer out of the office.

Meyer sat beside Deschler in the courtroom. Dark oak panels covered the room like a great wooden jacket, insulating it both from the cold and the sounds of the outside world. The room smelled of polish and reeked of institution and formality. Meyer loved courtrooms. They gave him the same feeling of warmth and contentment afforded by stepping in to a library.

The jury had not yet been led in and Deschler was looking through his notes in silence, formulating the arguments and points which he would be attempting to convince the jury with, as well as the final questions which he would be putting to the witnesses.

A door opened at the side of the courtroom and the jury were led in from an ante-room by a clerk, to take their positions. Deschler lifted his head momentarily from his papers and watched the men arrive and take their seats. His eyes then shifted to Meyer.

“All I require from you today is to pass me any of my papers if I require them. If I need a drink of water, you will pour me one and pass me the glass. Your job today is to make it possible for me to concentrate on this case without my thoughts being interrupted unnecessarily.”

Deschler looked back at the jury and studied each face in turn before continuing.

“I will brief you on the papers I will need and what you should be doing while I am either questioning or presenting evidence.”

He then started to move the papers around and place them into different piles. Once he was happy with how they were arranged he took off his spectacles and rubbed the scarred eye with a handkerchief. Then he placed a hand flat down on one of the piles of papers.

“You haven’t spoken since we arrived. That is a good start,” said Deschler. “These papers are notes that I have made which I will occasionally refer to. If I need them I will point to them and you will hand them to me.”

Deschler moved his hand and placed it on another set of papers. Meyer noticed that the tip of Deschler’s little finger was missing.

“These I may not need; however, they contain the names of all the witnesses as well as the individuals in this case. As I am cross-examining the defendant or making my statements to the court, you will constantly check the list and find the person I am discussing. If I need more information on them I will take this list from you and you will indicate on the page where that person’s name and details are.”

He now moved his hand to a third pile.

“These are questions I will be asking throughout today. I may ask additional questions. I may ask different questions. But these are the core for today. You will follow these and as they are asked you will indicate on the paper that they have been asked. If I need them I will point to them. You do not need to do anything more and I am sure you have assisted in this manner before.”

Meyer was about to reply to Deschler when there was an announcement from the Clerk of the Court that Judge Koehler was entering. Everyone stood until the judge was seated.

Very soon after that, Deschler’s client, Prala Weide, was brought into the courtroom by an officer and was taken to the dock, where he was seated. Meyer was familiar with this process, having witnessed it many times as a law student and as an intern, but this was the first time he had been part of the actual performance.

After some shuffling of papers and discussions with the Clerk of the Court and the stenographer, who showed the judge part of the transcript, the Clerk of the Court called for silence and the judge called the court to order.

Deschler pushed himself from his seat and made a short statement to the court regarding the case so far, how he had shown that the accused was innocent and could not have committed the crime, and that he would provide irrefutable proof to that effect. He then sat down again and waited for Prala Weide to be called to the witness box.

Prala Weide looked like a Gypsy. His long nose and swarthy skin was complemented by his greying black shiny hair and drooping moustache. His dark, almost black, eyes were sunk below thick, bushy eyebrows. His clothes were also dark, and slightly grubby in appearance. Although small in stature and with a withered left arm, he was obviously a strong, fit man.

After a few minutes, Prala Weide was called to the witness box, where he was seated and reminded of the fact that he was still sworn in. Deschler pushed himself up on his stick, which he then hung on the table. Meyer set the papers with the questions to one side, picked up the papers with the list of names on them, and waited for Deschler to speak.

“Your Honour, officials of the court, members of the jury, today I will finish my cross-examination of my client and be able to show that not only was he not able to have committed this crime, not only was he not present at the time of the crime, but that only one other person could, would, and did commit these terrible murders at the Färber family home.”

Meyer swallowed hard. He felt nervous and excited. Bauer had known what he was doing, having him start his new job on the last day of a murder trial. And with such an orator as Deschler to provide his first real lesson in the dark art of criminal law.

Deschler continued with his opening statement of the day.

“Dieter Färber, the Färbers’ youngest son and the only one still living at the same address, returned home to find his father and mother murdered in their living room. The room was in disarray, with ornaments scattered and broken on the floor, including a jar, which normally sat on the mantelpiece and contained a hundred or so Reichsmarks.

“In his state of shock and grief, Dieter Färber quickly checked the rest of the home, which had also been ransacked. On his return to the living room, Herr Färber saw a male Gypsy attempting to leave through the front door. Herr Färber then saw the Gypsy make off in a westerly direction towards the church.

“According to Herr Färber’s report to the police, this Gypsy had dark features, wore dark clothing, may have had an earring, and wore a kerchief on his head. A description of a Gypsy which could have been taken from any story book.

“We have already discovered that although Herr Weide was in the area of Herr and Frau Färber’s home at the time of the murders, Herr Weide was with another member of the Gypsy community. We have also discovered that Herr Weide was in possession of a large sum of money, from the sale of a horse.”

Deschler then paused and pointed to the papers containing the notes he had made from the trial. Meyer quickly picked them up and handed them to Deschler, who then took a few moments to study them before turning to his client.

“Herr Weide, can you remind us of your movements on the day you were arrested?”

Prala Weide cleared his throat and, with a deep voice and thick Romany accent, replied, “In the morning, after leaving the family, I took a cart horse to sell to a family camping in the north of Berlin at Mauerpark. We had agreed to meet at the flour mill in Ritterstrasse. I walked with the horse, not riding, and took him to the flour mill and waited.”

“And you were on your own on this journey?” asked Deschler, which Weide confirmed. “Where are you and your family camped, Herr Weide?” he asked.

“Sommerbad Kreuzberg. It is a small, wooded area, but very quiet. And the police leave us alone there as long as we don’t stay for too long.”

Deschler ran his fingers across his moustache before asking the next question.

“What time did you leave your caravan, Herr Weide?”

“It was four thirty in the afternoon. I am certain of this as I wanted to leave plenty of time to reach the mill, and I also spoke with my wife about my time of return.”

“And what time did you meet at the flour mill?”

“We were to meet at five o’clock at the mill. I was there ten minutes early.”

“So it took you twenty minutes to walk with a horse about a kilometre? That is a reasonably slow pace.”

“I had plenty of time; there was no need to rush the horse. I wanted him to look his best and strongest so I could get the best price.”

“Which route did you take Herr Weide? Did you pass Mariannenstrasse?”

Prala Weide shook his head.

“It is nearby but in the wrong direction. It would have added another, maybe, ten minutes to my journey.”

“So you took the most direct route to your meeting?”

“Of course. Why would I take a longer one?”

Deschler smiled.

“Why indeed, Herr Weide? The prosecution has already tried to establish that you were in the general area. The fact that you were within ten minutes of Mariannenstrasse means that you were in the locality. Could you be mistaken? Could you have passed Mariannenstrasse?”

Prala Weide shook his head once more.

“No. I am not mistaken. I was not near Mariannenstrasse. There was no reason for me to be there.”

Deschler nodded and took the piece of paper he was holding, turned it over and placed it on the table before picking up another from his pile.

“Herr Weide, what was the name of the man you were meeting?” he asked.

“Josef Jauner,” replied Weide.

“Were you meeting him alone?”

“Yes.”

“And did he buy your horse?”

“Yes. For seven hundred and forty-eight Reichsmarks.”

“That is a very precise number.”

For the first time Meyer saw Weide smile.

“It was how the negotiations progressed,” he replied, with a shrug.

Deschler stroked his moustache before continuing.

“Were you happy with that price, Herr Weide?”

“It was a reasonable price for the horse, yes.”

“Remember you are not on trial for illegal horse trading Herr Weide, please be frank with the court about the price you were paid and the quality of the animal.”

The smile had left Weide’s face now and his deep Romany voice was much quieter as he gave his answer.

“I was very happy with the price. The horse was worth it mind you, but yes, I was very happy with the price.”

“Josef Jauner paid you in full? And in cash? No promissory note?”

Weide looked aghast.

“In full. In cash. Nobody Romany does business on a promise!”

Deschler made a mark with a pencil on the paper he was holding before continuing with the questions.

“How long did these negotiations over the price for the horse take?”

“I couldn’t be entirely certain but around twenty minutes, including the usual pleasantries.”

“Pleasantries?” asked Deschler.

“You know, asking about family health and so on. Passing on stories and news from the road.”

Deschler nodded.

“And after Herr Jauner had paid you and bid you farewell, did you go directly home?”

It was Weide’s turn to stroke his moustache.

“No, I didn’t go home directly. There are a few bars on the route and I thought that I would quench my thirst with a beer or two.”

“How many bars did you frequent on your journey home?”

“One.”

“Only one, Herr Weide?”

“Yes. Only one.”

“And why only one, Herr Weide?”

“I was arrested coming out of the bar next to the mill.”

Deschler turned over his paper and placed it face down on the desk.

“Thank you, Herr Weide. No further questions.”

Deschler sat down and Judge Koehler asked Fuhrmann, the prosecutor, if he had any further questions.

Fuhrmann stood and ran his fingers through his white hair, while reading notes through spectacles balanced precariously on the end of his nose. Without looking up from the paper he held, he asked, “Where is this Josef Jauner?”

Weide looked over at Deschler and then back to Fuhrmann.

“I don’t know.”

Fuhrmann blinked and finally peered over his glasses at Weide.

“The police also do not know where he is. Or where this,” Fuhrmann cleared his throat, “horse is.”

He was then silent for a few moments before starting his next question.

“I suspect that Josef Jauner does not exist and the money which was found on your person was from several crimes, some of which may not yet have been reported! Is this not the case, Herr Weide?”

Weide looked slightly shaken, before replying that Jauner did exist and that he did sell him a horse.

“No more questions,” sneered Fuhrmann as he sat down.

Deschler immediately stood up and indicated that he wished to call his next witness, Dieter Färber, the victim’s son, before taking his seat again and turning to Meyer.

“Have you been following the questions?” asked Deschler in a low voice.

Meyer thought that he meant the questions written on the papers he had shown him at the beginning.

“Yes, Herr Deschler, and these have been marked as you requested.”

Deschler’s eyes narrowed.

“Herr Meyer, if you think I am going to pat you on the back for being able to tick off questions as they have been asked then perhaps you would be better off working in a kitchen.”

Meyer felt his face flush.

“Herr Deschler, my apologies. I have misunderstood you.”

Deschler rubbed the scar on his eye and Meyer could see a vein in his forehead pulse with his heartbeat.

“Herr Meyer, you may be here as my ‘assistant’ but I am sure I could have found a prettier assistant if I had requested one directly from Herr Bauer. I don’t need you to do these menial tasks such as ticking off lists of questions or pointing out addresses and names of witnesses. It is mildly helpful but not a requirement.”

Deschler’s voice lowered even further and Meyer strained to hear every word, although the meaning was clear.

“You are here to learn, Herr Meyer. To learn. Anyone can memorise the rules of law. Anyone can ask questions. You might even be able to ask the right questions. But working as a defence lawyer is not about what you ask. It is about how you ask it.”

Deschler took a deep breath and looked directly into Meyer’s eyes. He must have seen the disappointment that Meyer felt in himself. Deschler was right. It didn’t really matter if he managed to keep up with ticking off lists of names and attributed questions. That was a clerk’s job, and a stenographer was in the court making a full transcript of everything that was said. Meyer was a lawyer, and he should be learning the techniques, especially from a man such as Deschler.

Deschler’s voice softened.

“Ask some questions that you would expect the prosecution to ask but in a way which allows your client to give an answer you would like. I asked Herr Weide several times about his journey that day, finishing with asking him if he was mistaken. Of course he wasn’t mistaken and would never admit to being mistaken but this allows the jury to see you as pushing the point to its foremost conclusion. Juries expect lawyers to be confrontational, even with their own clients. You must not be seen to be giving your client an easy time in the witness box. In fact, if you can appear to be harder on your client than the prosecutor, the jury will accept the answers you have provided for them and may take the prosecutor’s apparently softer questions as an indication of innocence.”

Meyer nodded and managed a small smile. Of course, it seemed so obvious when Deschler pointed it out. It was all technique. Like Bauer being able to take Meyer’s train of thought down his own tracks to a dead end, Deschler was showing Meyer how questions were asked. It was as if he was being given the secrets to life itself.

“Did you notice anything about the papers I used during my questioning?” asked Deschler.

Meyer ran through the last few questions in his mind, like the re-running of a cinema film. What did Deschler do when asking the questions? Where were the papers? In his hand. In his left hand. He held them tight in his left hand and looked down at them occasionally. Then they were discarded. Face down. He turned them over at the end of a series of questions and placed them face down on the table.

“You discarded the pages face down on the table when you finished each area of questioning, Herr Deschler.”

Deschler leaned closer to Meyer, his eyes betraying a smile that did not sit on his lips.

“Turning over a page and placing it face down puts a full stop on a series of questions. The jury will naturally see that gesture as the end of something. It helps them to understand that you have made your point. That there is nothing else that could possibly be understood from any further questions on that particular subject,” explained Deschler in a whisper.

“Use this technique when you can. If you are lucky, and this is luck, the prosecutor may also unconsciously see this as an end to questioning and be unable to formulate any further questions of his own,” he continued.

“Unfortunately, in this case, Herr Fuhrmann does not allow such things to trouble him.”

The clerk of the court brought Dieter Färber to the witness box and reminded him that he was still under oath.

Deschler stood and smiled at Dieter Färber. This time his eyes showed no smile. The smile that sat on Deschler’s face was a lie.

Auschwitz, 24th July 1943

AFTER being photographed and catalogued, Meyer followed Kapo Langer to his hut and stood outside, along with the other men. The Kapo turned and stood with his arms folded, barring the way in through the door.

“This is hut number seventy-two,” he said as he pointed to a faded number ‘7’ and an almost imperceptible ‘2’, both painted in what would once have been blood red but was now a rusty brown, flaked and nearly impossible to read.

“This is my hut. It was built for a hundred men. It holds four times that number and is now your home.” He turned and pushed open the door, beckoning the men to follow him inside. The air was stifling in the summer heat. The smell of sweat and urine was oppressive and spilled from the wooden building to cover the waiting disinfected men with its putrid stench, making Meyer turn his head to try to get a lungful of cooler air.

He took a deep breath and forced himself inside with the others. Sweat began to form on his forehead immediately, and he let out the spent air from his lungs and tentatively took a short breath. He could taste the filth.

The wooden walls inside the hut had faded to grey, and mould and dirt covered the glass panes that remained in the windows, most of which were boarded up or cracked. The floorboards were filthy with dried mud and dust, and dirt lay in piles against the skirting. The ceiling was the direct underside of the roof and was stained from rainwater; white clouds from salts which had leached from the wood, and with fingers of black mould. Filling the room were stacked sets of wooden bunks. Most were three bunks high but some had four.

Langer held out his arms, and with them outstretched and his index fingers pointing, he slowly turned, as if proud of the dirty, decrepit building.

“This is my hut. Where you sleep and where you will probably die. I will outlive all of you. But, I will try to keep those who help me and, how can I put this, ‘work with me’, alive as long as possible.”

He dropped his arms and looked at the men before him.

“You get up at four am. You go outside no matter the weather and line up. This is for my roll call. Once I have a list of all those present I check the hut for those not there. I mark the sick and the dead.

“You stay standing in line until the SS do their roll call. They have the dead and the sick removed from the hut. We don’t see them again. Ever.

“You then get water to drink and are split into working parties by me. You go and do your work and return at a time determined by the guards. You go to the mess hut. Eat, drink. Come back to the hut and sleep.

“Then the same the next day. And the next day. There is no day off. There is no Sabbath.”

Langer looked from one face to another. This was a little speech that he liked giving. There was something powerful in telling men that they would live in misery and that this is where they would die. It was the most power he had ever enjoyed.

“You go now to the mess hut and pick up a bowl and a cup. Wait in the queue with these. No cup, no water. No bowl, no food.”

One of the other men spoke up.

“Which of these are our bunks?”

Langer’s brow deepened and his eyes darkened.

“You call me ‘sir’ when you speak to me.”

The man who had spoken stepped forward, and for a moment Meyer thought that he was going to challenge Langer’s authority. But instead he apologised for his disrespect and asked his question once more, this time adding ‘sir’ to the end of the sentence. This placated the Kapo and he laughed as he answered.

“Where are your bunks?” repeated Langer, and pointed around him, laughing.

“You can sleep where you want but you might need to do a bit of negotiation with the man who feels that you are sleeping in his bunk.”

Still laughing, he walked out of the hut in to the relatively cool air outside. “Come with me,” he commanded, “I will take you to the mess hut.”

His band of new inmates followed him.

“The first of the work parties will be back now. Let them eat first. Then you get your cups, bowls and meal. If I see any of you jumping the queue…” and Langer drew his finger across his throat.

“That is the latrines,” said Langer, as they passed a brick building from the days when this had been a Polish barracks. “Working there is a punishment. Being in this camp is a death sentence, but the only thing that will kill you faster than working in the latrines is an SS bullet.”

Langer took them across the dusty compound to the location of the mess hut. A line of grey-striped men stood waiting for their food. There was an eagerness behind the sunken eyes and dirty faces as they all stared at the queue in front of them as it slowly moved forward. Those at the front scurried off like rats to corners of the yard to eat their only meal of the day.

The new men were ignored with only a cursory glance as they were led to the back of the queue by Langer, who then walked off to the brick buildings near the entrance gate.

None of the men talked. There was no chatting. No jokes. No laughing. Only the occasional cough or sneeze broke the silence of the men. And forward they slowly but surely moved, one eager step after another as they got one place closer to the front of the queue and food.

Meyer moved forward one step, sometimes two or three steps at a time, until he reached the table with the piles of tin bowls and cups. Each man picked up one each and resumed their slow march to their edible reward for a hard day’s work.

Slowly, they shuffled forward and the dust from the camp settled on Meyer’s prison uniform. With every speck of grey he lost some colour. He could see it happening before his eyes. He wondered how long before he looked like the rest of the prisoners.

Meyer finally made it to the front of the queue and held out his tin bowl. The prisoner behind the counter poured a ladle full of thin soup into it, and a piece of black bread was unceremoniously dumped in the middle of the bowl, splashing some of the soup onto Mayer’s wrist. He then copied the man in front and filled his cup from the top of an open water barrel.

Meyer then found a corner to sit in before quenching his thirst with the cool water. He then devoured the thin soup and black bread. It was insubstantial, but he hadn’t eaten for so long that to Meyer it tasted like food at the best restaurant in Berlin. It did not take long before it was finished. He looked into his empty bowl and ran his finger around the edge to pick up any of the watery soup which had stuck to the metal. He sucked his finger, enjoying the faint taste of salt and perhaps chicken. He surprised himself, feeling his heart fill with joy as he spotted a reasonable size crumb of black bread which had stuck to the underside of the lip of his bowl.

Once he was certain that every single morsel of food had been consumed, he then made his way to the back of the mess hut and dropped his empty plate and cup into a pile of dirty crockery as he had seen the other prisoners do and started to make his way back to the only place he could imagine going in this hot dismal place, hut seventy-two.

Berlin, 18th November 1929

KURT Deschler took his time before asking Dieter Färber his first question. “Herr Färber, it must have been a terrible shock finding your parents in their home in that manner.”

Färber agreed that it had been terrible, and that it was something which would stay with him for the rest of his life. Deschler declared his deepest sympathy for him and continued with his questions.

“You lived with your parents, Herr Färber?”

“Yes.”

Deschler frowned and pointed to one of Meyer’s piles of papers, which Meyer diligently handed to Deschler.

“But I have it here,” said Deschler, pointing to the top paper, “that you were married two and a half years ago. Is this not the case?”

Färber looked confused and, in an embarrassed voice, admitted that he was married but that his wife had left him.

“What is your profession, Herr Färber?”

“I work in the meat factory, bringing in the carcasses from the wagons.”

Deschler nodded.

“That would explain your powerful frame, Herr Färber.”

“You need to be strong to carry in that meat.”

“Your father was also of a strong build, was he not? Being in the same trade,” asked Deschler.

“That is correct,” replied Färber. “Even though he was twenty years my senior, he was a very fit and strong man.”

“So it would have taken a particularly strong man to have been able to…” Deschler made a show of searching for the correct words. “Disable him?”

“Yes, of course.”

“Perhaps not someone with a withered arm?”

“We have already heard from you about that dreadful moment in your parents’ house, and I do not wish for you to have to relive it, but can you explain to me when you saw the defendant?”

Färber looked up to the vaulted ceiling and closed his eyes in thought.

“It was as I was about to leave the house. He was at the front door, opening it to escape. I tried to shout but I am ashamed to say that nothing came out.”

“Did the defendant see you?”

“I don’t think so, but he left very quickly.”

Deschler pointed to one of Meyer’s piles of papers. Meyer handed it over. Deschler picked one paper out and handed the rest back to Meyer.

“I have here the description of the defendant that you gave the police. Let me read this to you. ‘A Gypsy with black hair, pulled back into a ponytail. A black moustache, bushy eyebrows above brown eyes, a long nose, pierced ears and swarthy skin. He wore a black leather waistcoat, a patterned kerchief around his neck, a red shirt and black trousers’.”

Deschler handed the paper back to Meyer.

“That is a very convincing description of Herr Weide, don’t you think, Herr Färber?”

“Yes, it is. It is what I saw.”

“But you didn’t mention Herr Weide’s withered arm.”

“I didn’t notice it at the time. He was escaping through the door. It was all so fast.”

“Can I ask you, how did you know he was a Gypsy?”

Färber looked over at the jury and back to Deschler again.

“Well, I suppose I just guessed. He looked like a Gypsy.”

“Yes Herr Färber, your description is an excellent one of a Gypsy. Actually, a very typical description of a very typical Gypsy. How did you know he had a moustache and brown eyes?”

Färber looked puzzled.

“I am sorry, I don’t understand what you mean.”

Deschler’s smile had entirely gone now.

“How did you know what Herr Weide’s facial features were when you were not even certain if he had seen you? Herr Weide would have to be facing you for you to have seen the colour of his eyes.”

“Perhaps he did see me, it doesn’t really matter, does it? He was hurrying to get out of the house,” replied Färber.

“Oh yes, Herr Färber. It does matter. In fact, this whole case rests not on whether you saw someone running from your house, but whether they saw you. For you to be able to determine the colour of someone’s eyes, or the type of eyebrows, or the length of nose, then that person needs to be facing you, with their eyes open. You said that you were ‘unsure’ if he had seen you, but to be able to give such a detailed description you must have been staring into each other’s faces. Would you not agree, Herr Färber?”

Färber began to stumble over his words as he said that he did not know.

“In fact, Herr Färber, I suggest to you that you did not see Herr Weide in your parents’ home. I suggest that there was no break-in on that day. I suggest, Herr Färber, that in fact it was you that required the money from your parents to cover gambling debts. The very same gambling debts which had only recently meant the loss of your home and, subsequently the loss of your wife. You chose a Gypsy to blame this crime on, but unfortunately for you, the police found a man fitting your schoolboy description of one; Herr Weide, thereby requiring a trial and full investigation…”

Fuhrmann the prosecutor jumped to his feet and exclaimed, “Your Honour, Herr Färber is not on trial, he is as much a victim as his poor departed parents.”

Deschler continued to talk through the interruption, his voice rising above both Furhmann’s and the judge’s.

“It would have been much better that this go as an unsolved crime, especially at this time of uncertainty while the police have much more on their plates with communists and fascists fighting in the streets!”

Finally, Judge Koehler’s voice rose above the melee.

“Herr Deschler! You will desist! Herr Färber is not on trial; this is conjecture on your part!”

Deschler apologised and sat down, while Judge Koehler indicated to the jury that they should ignore the last few statements from Deschler and asked the stenographer to strike them from the record. But the damage was done. Meyer was in awe of Deschler’s ability to manipulate the witness and the jury, twisting the story to fit his needs. He had given the jury everything that he had told Meyer they required, even an alternative suspect.

Once everything had calmed down again in the courtroom, Judge Koehler asked Deschler if he had any more questions. Deschler pushed himself back up on his stick.

“No more questions, your Honour, and no more witnesses. The defence rests.”

Fuhrmann did not follow with any questions. Meyer looked over at the prosecution bench to see Fuhrmann sitting back in his chair, flicking through the contents of a cardboard folder. Meyer was sure that Deschler had won the case and had expected to see the prosecutor furious, especially with that final ambush at the very end of the trial, but he seemed serene, possibly even resigned to the loss of the case.

Meyer sat back in his chair as if winded by a blow to the stomach. He turned his head to see Deschler’s reaction and was surprised to see calm placidity across his face. Meyer could not understand how Deschler was able to accept the verdict.

The jury had been out for two hours before returning with a majority verdict which found Prala Weide guilty of the murder of Herr and Frau Färber but not guilty of theft. The judge read out the verdict of the jury and then dismissed the court to be reconvened in four weeks’ time, at which point he would give sentence.

Prala Weide’s face had not changed when the verdict was read out. It was as if he was not in the least surprised to be found guilty. Even with Herr Deschler’s defence, which Meyer had thought was masterful, even though Herr Deschler had shown that there was no real evidence against him and had provided the jury with a possible alternative suspect, he did not seem surprised.

“I don’t understand,” said Meyer, quietly, as the court rose and Judge Koehler left the courtroom.

“What don’t you understand?” It was Deschler. Meyer had not realised that he had spoken out loud.

“I thought we were certain of winning,” he replied.

Deschler’s normally stern look softened. He had noted Meyer’s use of the word ‘we’ when talking about the loss of the case. Not ‘you’ but ‘we’.

“Help me pack up and carry these papers back to the office,” said Deschler. “You say you don’t understand the verdict? It is quite simple. We didn’t have much of a chance of winning this case, right from the beginning.”

Meyer started collecting the piles of papers and returning them to their cardboard boxes.

“What do you mean, Herr Deschler? How is it possible that we didn’t have a chance from the very beginning?”