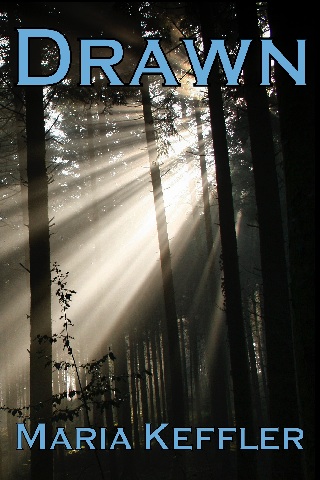

Description:

Artistic prodigy Juliet Brynn wants to survive 1982 with as little social torture as possible. But then her sketches start to come true and Damon Sheppard, a boy with a troubled past, shows her worlds she never knew existed. When unthinkable trauma strikes, will Damon and her prophetic gift prove as catastrophic as some predict, or can they impart Juliet the power to make everything right again?

“I started to pray for help to come, for God to save us. Then I stopped. I swallowed another mouthful of my own blood. If God even existed, he obviously didn’t give a crap about me.” — When Juliet begins to shape the future by drawing it, she must discover the source of her newfound power of artistic prophecy and the key to making it work. But when her trust and her future are betrayed by the very people who condemned Damon, she must learn to discern right from wrong, truth from deception, the honorable from the predatory. And when everything she knows and loves is taken from her, she discovers a power at work in the universe which forges paths into places most people choose never to go.

Book Rated: G

Maria Keffler

e x c e r p t

[Web-Dorado_Zoom]

DRAWN

Maria Keffler

CHAPTER 1

Wads of hot pink taffeta and starchy crinoline bunched between my thighs as my knees pumped up and down – right, left, right, left – and sweat seeped out of the stiff underarm seams between the dress’s bodice and its puffy, ribbon-bound sleeves. The flat soles of my black Mary Janes kept slipping off the pedals, and the third time my leg flew forward it scraped the rim of the front wheel and snagged the inside of my calf. My stocking caught on it, ripped open, and the run zippered all the way up to my inner thigh.

Was it too much to ask for a ride?

By the time I got to school I raged at Dad for teaching a night class on Fridays, at Mom for signing up for a business development seminar tonight, and at Mark for having more dates than a Christmas fruitcake.

I locked my bike in the rack, wiped the sweat off my face with the inside of my skirt, and smoothed everything out as best I could. I unclipped Nonnie’s antique barrette and laid it on my bike seat as I finger-combed my hair. The rows of multi-colored jewels sparkled under the moonlight. I slid it back on and hoped my hair had finally gotten thick enough to support its weight.

With a deep breath I went inside and followed the sounds of laughter and music.

The first week at Parnell Junior High always ended with the Back-To-School Dance. I’d dreamed about it since the fourth grade: clusters of lilacs and roses on linen-draped tables; tall boys in tuxedos and shiny black shoes that clicked when they walked; elegant girls in shimmery gowns that swirled as their partners danced them masterfully across a glossy marble floor.

And I would be the most beautiful of them all. Juliet Brynn, the belle of the ball, envied by girls and studied by boys with smoldering eyes and half-smiles that dimpled their square-jawed cheeks and revealed the one weakness in their chiseled, masculine armor: me.

My seventh grade dance? A huge disappointment.

This year’s looked no better.

The gymnasium smelled like it always did. Armpits. Dirty socks. Dolph’s homebrewed pine-ammonia-moonshine cleaner. They repainted the floor over the summer, and the tang of polyurethane stung my nostrils.

“Hey, Juliet.” Amica Aldridge walked past and snorted as she looked back over her shoulder. “Nice outfit.”

Bethany Howard and Tori Wetherton followed her to the center of the gym. Squares of light off the mirror ball flickered all around them.

All three wore black or dark gray dresses and looked about ten years older than the rest of us. Amica played with her diamond pendant as Tori whispered something and they all laughed. Bethany tossed her head and thick auburn curls spilled over her bare back. They swayed to the music, vigilant dragon-beasts hungry for a sacrificial innocent.

Most of the time, that was me.

I looked down at myself, grateful for the semi-dark and the flickering mood lights beside the D.J. stand.

Knobby knees poked out under the crumpled skirt of the bridesmaid dress Mom found at a garage sale, and my shoulder blades stuck out farther in back than my chest did in front. According to my stupid brother someone screwed my torso on backwards. And when mom found the package from my Better Bust Beginner’s Bra in the trash, she told me, “Only God can make something out of nothing.”

Other than the three dragon-girls in the center of the gym, however, no one else looked much better than I did.

The astoundingly un-dashing boys not only failed to wear tuxedos, but few of them even changed out of the T-shirts and sweatpants they’d worn to school that day. Some hovered around the punchbowl and crushed pretzels over each other’s heads. Others kicked and punched each other in the hallways like a bunch of retarded Ninja wannabes. Two eighth-graders snuck up on a seventh-grader and pulled his underwear so far up his back that the poor kid screamed, clutched his crotch, and fell to the floor on his face.

The girls mostly clustered around the walls and stared at the boys.

Only the party kids hung out co-ed. A few slipped behind the bleachers as Mr. Tollin argued with Miss Downey and someone’s mom confiscated a pack of bubblegum from a kid next to the D.J.

“Hey,” came a voice behind me.

I spun around.

“Oh. Hey.”

Lucas Emberry thrust an enormous hydrangea into my face. “I brought you this.” He shifted back and forth on his creaky sneakers. “It’s no big deal. My mom has, like, twenty bushes of them. I just thought, since it was the first dance of the year. You know.”

“Thanks.” The flower obscured Lucas’s entire head. Its stem hung down two feet. I tried not to touch his hand as I took it. “I’m not sure where to put it.”

“You want me to stick it in your hair?” He lurched at me.

I scuffed backwards. “No. I’ll just hold it. Maybe between my teeth, if I tango or anything.”

“You’re hilarious!” Lucas snorted, then stuffed his hands in his pockets. “And you look really pretty, too.”

Why couldn’t someone cool like me?

“How was your first week?”

“Okay, I guess.” I looked past his beet-red, cauliflower ears for Tammy or Lula.

“You’re probably in advanced art, huh?”

“Yeah. Painting.” Jimmy? Pam? Anyone?

“My dad’s taking me to the Sci-Fi Festival in Chicago next weekend. How cool is that? We’re going as Klingons.”

I refocused and saw two of my flame-pink self in the frames of his glasses. “You’re going where? As what?”

He stepped back, clutched his chest and screeched like a wounded hawk.

“The Science Fiction Festival? Star Trek?” He thrust his hand in my face and made a V-sign with four of his hotdog fingers. “‘Live long and prosper’.”

“I think my brother watches that.”

He shook his head. “You’ve got to go. It’s the best! You want to come?”

A Billy Joel song ended and the notes of a Foreigner ballad echoed off the walls.

Don’t do it, Lucas.

He stopped grinning. He lowered his chin. He reached his upturned palm toward me. “Do you want to da—”

“I’ve got to go to the bathroom.”

I spun around and smacked into something warm and hard that smelled really good. A field of azure blue, and the words DIVE and PROS in white block letters, stretched across the bridge of my nose.

Hands grasped my upper arms as I stumbled back. My heart thudded in my temples and my legs went limp as spaghetti. A strange, electric sensation buzzed around in my head, then fizzed up and out the top.

“You okay?”

His shirt read DIVE PROS BRISBANE and smelled of wind and leather. “You’re really tall.”

“Maybe you’re really short.” He let go of me.

Then Lucas’s thick fingers spread across the small of my back. “Are you all right, honey?”

Honey?

The cretin cupped my elbow in his other hand as the wall I’d walked into walked away.

I brushed Lucas off and kept wiping to get the sensation of him off my skin. “‘Honey?’ What was that?”

“Maybe you should sit down.” He tried to get his arm around me again.

“I’m fine.”

“Your nose is bleeding.”

A drip slid out of one nostril and over my upper lip. “Oh, crud.” I threw my head back and swiped the blood upward with my finger.

Someone screamed.

“I’ve got her!” Lucas barked and tried to pick me up.

“Stop it!”

“Get back. Let me through.” Mr. Hirschman’s face blocked my view of the ceiling. “What happened?”

“I bumped into somebody.” I sniffed up a glop of blood. “I need a tissue, that’s all.”

Mr. Hirschman waved across the gym. “Let’s get the nurse over here!”

Amica shimmered in the corner of my vision. She pointed at me with one finger and covered her mouth with her other hand. The dragons swayed their heads into each other and hissed fire. Voices circled.

“What happened? Is she okay?”

“Ew, gross!”

“Give her some air!”

Oh, give me a break.

* * * * *

“It was horrible, Kitty.” I bounced the coiled phone cord against the floor and tried to get it to hit the ceiling.

“It couldn’t have been that bad. He probably didn’t even see.”

I switched the phone to my other ear and tucked it against my shoulder. I put my grandmother’s barrette back in its loop on the lampshade and grabbed a pencil and sharpener. “Everyone saw. You couldn’t help but see. They practically put me in an ambulance.”

She laughed. “You exaggerate. Tell me what he looked like.”

What did he look like? All I could really remember was his shirt, his height, and the way he smelled. “That’s weird.”

“What?”

“I can’t remember his face. I never forget stuff like that.”

“Yeah. That is weird.”

“But he had a great voice. He said I was short.”

“You’re not that short.”

“How do you know?”

“I’ve seen pictures.”

I twisted the sharpener around my pencil a few times then tossed it at the desk. It landed on the floor next to the pile of stuffed animals between the wall and my dresser. On a blank page in my sketchbook I feathered in the outline of a T-shirt. I lingered on the arms, and probably made them bigger than they actually were.

“You’re drawing him, aren’t you?”

“Kind of. Maybe his face’ll come back to me.”

My bedroom door swung open and the loose top corner of my Scott Baio poster curled down over his shoulder and the beach towel draped around his neck.

“Mom! Would you knock, please?”

She put up her hands and whispered a melodramatic apology. “I need the phone.”

“Right now?”

“Yes.”

I sighed. “I’ve got to go. I’ll put your letter in the mail tomorrow.”

“Can’t wait to see it! I sent you one yesterday.”

“See you.”

“Juliet?”

“Yeah?”

“You’re about to get a really cool gift.” She hung up.

I dropped the handset in the cradle and gave Mom a dirty look. “There. All yours.”

“Kitty, right?” Mom looked around and sighed. “You need to pick up in here.”

“I know.”

“If anyone saw this room no one would ever hire me.”

“Whatever. You don’t even have any clients yet.”

She nodded. “Maybe you’re the reason.”

“Like your clients are ever going to see inside our house.”

“And I thought you and Kitty were pen pals.”

“Yeah.”

“Then why so much time on the phone? I’m going to start charging you for the long-distance.” She picked up my pajama pants and turned them right side out. “You have local friends, too. What about Jimmy and Mia? You hardly saw the twins all summer.”

“Just leave my stuff where it is.”

She laid the pants at the foot of my bed. “What are you drawing?”

I closed the sketchbook. “Nothing. It didn’t come out.”

“Since when does anything not come out? Can I see?”

“There’s nothing to see.”

She folded her arms over her waist and sighed. “I miss when you were little and you brought me every picture you made.”

I rolled onto my stomach. “I’ll do something for you. Something good. What do you want?”

“It’s not that.”

Downstairs the front door opened and shut again.

“Dad’s home.”

“Mm-hmm. I need to make those calls.”

When she left I went to the window. This amazing thing happened, and I had no one to tell.

I closed my eyes. Come on, memory. I leaned against the window casement and replayed it. But I still couldn’t see him, and I let it go too long. The nosebleed. Laughter.

Nothing wonderful ever stayed wonderful. “Why does it always have to be this way?”

The mattress caught me as I fell back, arms over my head. “I wish I could make it different. Make things happen better.”

In the sky outside my window a star winked blue, then red, then blue again.

At least I could draw some of it. I took up my sketchbook and pencil and pretended to talk to Kitty. “Too bad you weren’t here. He had the best arms I’d ever seen on any guy who wasn’t at least five years older than us.”

I started to fill in the T-shirt with DIVE PROS BRISBANE, then stopped. What if someone saw it? “What should I put there instead? What do I like? What would make him even cooler?”

“Einstein.” I fuzzed in wild, gray hair. “He’s smart. And athletic and mysterious.”

What will he say next time you see him?

I drew a word bubble over his blank face.

“What will he say?” I asked out loud. Then a line from a silly sitcom popped into my head. “If we keep crashing into each other like this, we’ll have to start filing flight plans.”

I giggled, turned to the next page and sketched two jetliners about to collide. “Two jumbo-jets crash into each other in mid-air.”

I ripped the pages out of my sketchbook and tacked them to my cork wall just as Nonnie’s barrette fell off the lampshade again. I rolled off the bed, picked it back up and got this weird sort of shock. Not so much like from static, but more like a warm, fizzy sensation that shot up my fingers, through my spine and out the top of my head.

“Weird.” When I slipped it through its loop it swung back and forth and sparkled, red, blue, green and gold.

That night I dreamed Albert Einstein took me to homecoming. When he kissed me the glitter ball fell down on my head and turned into the homecoming queen’s tiara. I bowed and blew kisses as everyone tossed roses at me. Then I took off the crown and threw it into the sky.

A dragon swooped down from the clouds, caught it between its teeth and ate it in one gulp.

* * * * *

I covered my letter in one of Kitty’s favorite motifs. Two angels in flowing robes reached toward each other across the front of the envelope, and I wrote her address in the drape of one of their sleeves. The blond angel’s hair made curlicues around the stamp.

“Gotta go! I’m late.” Mark skipped the last couple of stairs and crossed the kitchen in three steps.

Mom yelled down from her bedroom. “Mark, you need to drop Juliet off at school!” But he didn’t hear. The car door slammed, the engine revved and his tires spit gravel as he sped down the street.

Typical.

“Can you drive me, Mom? Mark left.” I licked the envelope and sealed it.

“No! I’ve got a meeting. Ride your bike.”

“It’s at school, remember? You picked me up after the dance.”

“Then see if your dad can take you.” She closed her bedroom door and started the shower.

Dad didn’t teach on Mondays, and usually spent the day on research. I went down to the basement and knocked on his office door.

“What is it?”

“I need a ride to school.”

“Why can’t you take the bus?”

“There’s an art club meeting before school. We’re submitting stuff for a contest.”

He dropped something on his desk and sighed. “I’m neck-deep in work here. Just skip the meeting and go to the next one.”

I laid my forehead against the door. “There won’t be a next one, Dad. There’s a deadline.”

“There’ll be other contests. I can’t stop right now.”

I’d have to walk.

August humidity triggered every sweat gland in my body when I stepped outside. The weather didn’t care that summer ended. While we sat on hard chairs under fluorescent lights with totally boring textbooks and endless piles of mind-numbing worksheets, the sky continued to make days for swimming across lakes or eating warm elephant ears at carnivals.

Powder-blue chicory grew on twisted, hunter-green stalks on both sides of the chip-seal road, even after it turned to asphalt a mile toward town. Birds flitted from the tasseled cornstalks to twist-wire fences and up into apple and maple trees scattered around yards and fields. Brown and white cattle grazed between the road and an enormous red barn beside an old gas station. Wilbur Dugan stored hay and straw in the loft, and the smell always made me think of Halloween, when he turned the barn into a haunted house and held a dance in the corral behind it.

A blue Datsun pulled off the road in front of me. The passenger window rolled down and Jimmy stuck out his head. “You’re late!”

I ran to the car and jumped in the back with Mia. She balanced her science book on her legs and scribbled in a notebook on the seat. She’d already started on the next chapter, and the rest of us hadn’t even finished half the first one.

Mia snatched up her notebook, jammed it into the textbook, and stuffed them in her bag. “Hey, Juliet. I like your earrings,” she whispered.

“Thanks,” I said. “Thanks for picking me up, Mrs. Teele.”

Fire-engine red lips wiggled in the rear-view mirror. “You shouldn’t be walking by yourself, dear. Where’s your mother?”

I put my bag on the seat and looked out the window. “Mark was supposed to drop me off, but he forgot. Mom and Dad had other stuff to do.”

“Mm-hmm.” She shook her head. “We missed you in church last Sunday.”

Mrs. Teele kept better attendance records than the minister.

“Were you away?” she asked.

“Huh-uh. Dad had a headache and Mom overslept.”

She hummed her disapproval.

“Can I see what you’re turning in?” Jimmy reached his hand back.

“It’s at school.”

“You didn’t work on it over the weekend?”

“I finished it Friday, so Miss Downey kept it.”

Jimmy pulled a comic book out of his bag. The light struck its plastic sleeve at an angle that blinded me. I reached to move it out of the glare and he jerked it back.

“Don’t wrinkle it!”

“Don’t freak out.” I held out my hand and he passed it over. ‘The Adventures of Hart McSwain’? This is for Art as History?”

“It’s a pioneer story. How Hart McSwain and his five brothers conquered the West.”

“Mine’s really different from this.”

We pulled up to the school and Mrs. Teele dropped us off at the front door.

“Are you seriously already on chapter two in science?” I asked Mia. We sat next to each other in Mr. Holden’s class. He assigned seats at the two-person tables, one smart kid and one dumb kid. I didn’t have to wonder which one he thought I was.

“No.” She shook her head. “I was just looking at it.”

As we passed through the main lobby I checked out the office and down Halls A and B.

“Are you going to the Science Fiction Festival next weekend?” I asked Jimmy.

“Impressive that you know about that,” he said and tapped his index finger on his cheek.

“Lucas told me.”

“I see.”

I glared at him.

“Mom and Dad won’t let him go,” Mia said.

“Why not?”

“Because I’m not old enough.” Jimmy scowled at Mia. “It’s none of your business, anyway.”

“Whatever. I’ll see you later, Juliet.” Mia smiled at me and started to say something else, then turned and walked away.

Jimmy and I went down Hall C, toward the art classes. I scanned up and down the corridor.

“Who are you looking for?” Jimmy asked.

I snapped my eyes to the floor, too quickly. “No one.”

“J.B.” Jimmy stopped and crossed his arms over his chest. “Don’t treat me stupid.”

“J.T.,” I said. “I said no one.”

Miss Downey’s door opened. She squeezed a stack of white plastic paint pallets between her waist and elbow and balanced a gargantuan bowl of black bananas, shriveled apples, and moldy grapes on her shoulder.

“I’m glad you’re here. Grab the door for me, Jimmy.” She pushed it open further with the hip of her chocolate-brown broomstick skirt, then slid out as Jimmy grabbed the handle. She knocked the bowl against the doorjamb and a swarm of fruit flies alighted in a sizzling gray cloud.

“It’s not really still-life if the bugs are moving,” I said.

Miss Downey winked. “They force me to teach you to paint fruit. No one said it had to be fresh fruit.”

The art world, historically, is populated and driven by subversives. Art should do more than imitate or accessorize life; it should question the rules, stretch the boundaries, investigate the underlying truths behind who we are and what we do.

I got an A on my last art quiz for remembering that word for word.

Why, for example, must art students paint bowls of fruit? Just because they always have? Not according to Miss Downey. She tells us to paint anything that catches our attention, as long as we do so for a reason. That something is pretty or interesting is never a good enough reason to draw it.

The last couple of sketches I did wouldn’t impress her.

“Let me drop this off for the seventh-graders and I’ll be right back.” One of the pallets slipped out of her grip and clattered to the floor. She growled and kicked it with the embroidered toe of one of her lime and tangerine ballet flats, then punted it down the hall into Room 117.

“She should play soccer,” Jimmy said.

We went into the classroom and dropped our things on the front table. Jimmy opened his backpack and slid the comic book out between both thumbs and first fingers. He kissed its cellophane sleeve and laid it on the table between our bags.

“I really want that five hundred dollars.” He smoothed his thin hands over the plastic.

“A lot of kids are entering, you know. It’s statewide.”

Jimmy shrugged. “I know. But I put over eighty hours into this thing. I worked on it all summer.”

“Wow, really?”

Footsteps approached. My heart sped up a little bit, and I spun around to the doorway.

Stupid. Like he’d come to an art club meeting.

Lula’s voice echoed down the corridor followed by Tammy’s snorty laugh and Miss Downey’s humming. They all stopped just outside the door and Lula leaned close to whisper something to Miss Downey.

Miss Downey narrowed her eyes and clucked her tongue. “Don’t believe everything you hear.”

“So it’s not true?” They followed her into the classroom.

“Rumors usually contain a seed of truth sprouted in a field of fabrication.”

Tammy scrunched up her mouth. “But you’re a teacher. You could find out.”

“Find out what?” I asked.

“Nothing,” Miss Downey answered. “Least said, soonest forgotten. Let’s not add to his troubles, if trouble he already has.”

“Who?” I asked.

“Juliet, go get your canvas from my office. Tammy, I put yours there, too.”

We walked to the back of the classroom, into Miss Downey’s office. I grabbed Tammy’s arm. “What were you guys talking about?”

“The new guy. Where have you been?”

“What new guy?”

“Damon Sheppard. Where have you been all week? He’s in Sweeney’s homeroom.”

“What about him?”

“He’s a wild child,” Tammy whispered. “I heard he spent a year in detention before transferring here.”

“So?”

Tammy leaned in and almost touched noses with me. “They say he killed somebody.”

I frowned. “I think you’d get more than a year in juvie for that.”

“He’s only fourteen. He couldn’t be tried as an adult.”

“Sure he could. They do it all the time.”

She rolled her eyes and tsk-ed her tongue. “I’m just telling you what I heard.”

Tammy stared at me and I chewed on the inside of my lower lip.

Could Damon Sheppard be the boy I ran into at the dance?

“Maybe ask your dad,” I said. “Police can find out stuff like that, right?”

Miss Downey called from the front of the classroom. “Girls, we don’t have a lot of time.”

We took our canvases to Miss Downey. “Here are the info sheets that accompany these. Fill them out, attach them to your work, and you’re free to go. I’ll package them and I’ll make sure they’re postmarked today. The judges pick the winners the second weekend in October.”

Jimmy smiled. “So we’ll find out who won right after that?”

Miss Downey nodded. “I expect so.”

Lula turned the corner of my canvas to see the painting. “Wow, Juliet. That’s really beautiful.”

Miss Downey leaned over Lula’s shoulder. “Look closer.”

CHAPTER 2

“I am now distributing an orange sheet of paper, on which you will find the school calendar for the months of September and October, Anno Domini nineteen hundred and eighty-two. September is on the front and October is on the back.” Mr. Hirschman’s nasally voice quivered with an impending sneeze.

I drew a semicircular arch and trimmed the edges with thick stubble.

Pam Martz snorted right behind my head, “How do we know October isn’t on the front and September’s on the back?”

I filled in brows, eyes and a bulbous nose, and put more shading over the jaw and upper lip. A cleft chin with a fat mole under the lower lip. Black-rimmed glasses. “And he sneezes again,” I whispered. A word bubble over his head read, “Pardon”. Then I folded it in half and tucked it in my notebook.

“Please note, students, that September 17 is the deadline to… ”

He stopped, pulled a wadded handkerchief from his pocket and opened his mouth. Everyone in the first three rows slid down in their chairs. When he sneezed, a spray of droplets erupted out of his nose, as if his nostrils had a fan setting, like a garden hose. A rainbow glistened in the dusty swath of light from the window.

“Pardon.” He wiped his nose, blew into the rag again, stuffed it back in his pocket, and smoothed down his tie. “September 17 is the deadline to sign up for the Academic Olympics. That’s all the announcements. Take out your homework and turn to problem one. Miss Brynn, please write it on the blackboard.”

Of course, it had to be me.

I took out my notebook and stood up. On my way to the blackboard I passed between Bethany and Tori.

“Cute shorts,” Bethany said, and wrinkled her nose. “Did you get those at the Disney store?”

After more than a year I still hoped that one day they’d take me back and I’d be cool. One Friday we were all friends. Then I missed Amica’s first boy-girl party, and on Monday they didn’t like me anymore.

So I didn’t say anything. Instead, I turned red, and my ears got hot, and I tripped over an eraser on the floor, and my eyes watered, because people laughed and Mr. Hirschman didn’t even hear it since he sneezed again, and this time he got me wet too and all I wanted to do was go hide in the art room.

“Let’s go, Miss Brynn,” he said between wipes. “Problem number one, please.”

I went to the board and picked up a piece of chalk. My hand shook. “4x + 8y = 32.” I blinked to keep a tear from slipping down my cheek. “And y – x = 1.”

“Now, show the class how you solved it.”

I didn’t solve it.

I tried to solve it. I had two lines of work beneath the problem, but no answer. Mom didn’t know how to do algebra, and Dad said, “This is why I became a history professor. Ask your brother.” But I had the dance on Friday night, then Mark slept till one on Saturday, after which he rushed out to a movie with a girl, then he came home and took a nap and a shower and left for a date with some other girl.

“Miss Brynn, are you still with us?”

I wrote the first line I’d done beneath the two equations. “4x + 8y – 8y = 32 – 8y.”

“Very good. Keep going.”

“And y – x + x = 1 + x?”

Mr. Hirschman sat down at his desk and crossed one leg over the other. “Why did you do that?”

“It’s the same thing I did to the first equation.”

He held up one finger. “The idea is to isolate one of the variables. Not both of them.”

I bit the inside of my cheek. “I thought they’d be less lonely if they were isolated together.”

The class snickered.

“May I go to the restroom, please?”

I gave him the look. A male teacher never refuses a girl a bathroom break if she gives him the look.

He held out the hall pass.

I clutched my notebook and dashed to the door. I just needed a few minutes alone and some cold water on my face. I fled the room and turned left.

And I crashed into him again.

* * * * *

My notebook dropped and loose papers fluttered over the floor.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “Are you okay?”

“My fault,” I stammered and knelt down to pick up my stuff.

“Let me help.” He knelt down and picked up one of the papers. “If we keep crashing into each other like this, we’ll have to start filing flight plans.”

I stopped mid-reach. “That’s funny.” I looked in his face. He couldn’t have seen the drawing on my wall. Could he?

Did somebody else see it and rat me out?

“But you’re not smiling.” He leaned over and picked up the last paper. “That’s a good drawing. You’re really talented.”

“What did you say?”

“I said that you’re talented.”

“Before that.”

His face turned pink.

Do guys blush?

“I know, it was stupid.”

Mr. Hirschman came out of the classroom.

My sketch! He still has it!

The boy looked at Hirsch, then at me, then at Hirsch again. And he slipped the paper inside his jacket.

Who wears a leather jacket on a day like this?

“What’s going on out here?”

He handed Mr. Hirschman a hall pass. “I’m supposed to switch to your homeroom. So I can fit geometry into my schedule.”

He’s going to be in my homeroom.

“Geometry? That’s a challenging course. I should know, since I teach it.” Hirsch examined the paper in his hand. “Damon Sheppard. Weren’t you on your way to the ladies’ room, Miss Brynn?”

I wanted my sketch back. I pretended to organize my notebook.

“Do you have a transfer slip?”

“Right here.” He reached inside his pocket and his jacket opened up in front.

I fell back against the wall. No way.

Hirsch pointed to the boy’s T-shirt. “Very nice, Mr. Sheppard. We like Einstein around here. Miss Brynn! Either use that pass or get back to your desk.”

* * * * *

Erik Athaca, head of the class and first-string basketball player, pressed his science textbook open with one freakishly large hand while he scribbled definitions into a notebook. Across the table Drew Barony’s head rested on his elbow and he snored. I plopped down, opened my math book and sighed.

“Everything okay?”

How can popular guys be so nice but popular girls are such jerks? “Math. It’s always math.”

“Algebra’s not that hard.”

“So says you.” I opened up my book to the problems we had to turn in today. Hirsch gave me till seventh period to finish them or he’d mark them late.

Erik looked over at my notebook. “Maybe you can get half credit for doing half of all the problems.

“Very funny.” My eyes heated up and I bit my lip. Do not cry in study hall. “I just don’t get it.”

Erik shrugged. “I’d let you copy mine, but I turned it in already.” He grabbed my notebook and spun it around to face him. “It’s like Hirsch said, isolate one of the variables in one of the equations, then substitute the answer in the other equation.”

“Then what?”

He pushed it back to me and went back to his science book. “Then solve for the second variable. After you have a number, you plug that into the first equation and solve for the first variable.”

I slumped over and dropped my head on my notebook. “Why is math so easy for you?”

“Why is art so easy for you?”

“Art’s not hard.”

“So says you.”

I scowled. “Not being able to draw a tree won’t keep you out of college.”

“Art college, maybe.” He drummed his fingers on the table. “You should get someone to tutor you.”

Like Lucas?

Erik’s eyes got really big all of a sudden, like he just thought of something. “Hey. Are you signing up for the Academic Olympics?”

“Why would I?”

“We could use you this year. They added arts and literature, if you can believe that.”

The school brainiacs, playing Pictionary? “That doesn’t sound very academic.”

“Wait till you see some of the questions. Come by Hirsch’s room after school.”

“Maybe.”

* * * * *

I spent the rest of the morning jittery, sweat dripping out of my armpits as I prayed to run into Damon again. With only three hundred students at the school, I’d have to see him eventually, wouldn’t I? Maybe the rest of his schedule changed along with his homeroom.

He didn’t show up in English or gym. I didn’t expect him in art, though I jumped out of my seat when a brown leather jacket passed by the doorway. It happened so fast I couldn’t tell if it was him, but I made a mental note to get to art early tomorrow and keep an eye on the door, just in case.

Lunch happened in three shifts during fifth period, so that class lasted longer than the others. Fortunately, I had art then, so I didn’t mind the extra time. I also had the last lunch shift again this year, which hardly seemed fair.

Since we finished our contest entries, Miss Downey gave us a free painting day. Lula and Tammy worked on the other side of the room next to the oils cabinet. Jimmy started another comic book at his desk. I put my easel next to the watercolors and started a painting for Mom.

I penciled in four flowers growing out of a crack in some steps, then sketched a rose for my mother, a dragon lily for my dad, and a cattail for Mark. For me I drew a vine of moonflowers that twisted on the ground around the others. In real life, moonflowers would grab onto and climb up the other flowers, choking them in the process. But that’s one of the great things about art. You can make life do what you want it to.

“Lovely shapes, Juliet.” Miss Downey moved from one side of me to the other.

“They’re my family.”

She twisted one of the chunky rings on her hand. She pointed to the stairs. “Tell me about that.”

“It’s about how my parents met.”

Miss Downey tucked two straight hanks of long, brown hair behind her ears. Copper peace symbols studded with chunks of turquoise hung from her earlobes.

I dipped my brush in charcoal grey and watered it down to soften the color, then stroked it over the steps and twisted the brush as I painted. “My dad worked his way through college doing landscaping. My grandparents hired his company to put in a path from the driveway to the front door. He was laying the front steps in place when my mom came out. She was late and forgot to use the side door. She tripped over my dad and knocked four bricks out of the mortar. One fell onto the walkway and cracked in half.”

“And they fell in love at first sight and lived happily ever after?”

“Not exactly.” I got a bit of kohl black on the tip of my brush and outlined the cracked steps. “He was furious and she sprained her ankle. Grandpa yelled at Dad about it and took Mom to the hospital. While they were gone Dad put the cracked brick back in place and mortared it in.”

Miss Downey sat down on the table next to my easel. “Why didn’t he use a new one?”

“He didn’t have any left and he was too mad to make a trip back to the hardware store.”

“After that auspicious meeting, how did they end up married?”

“They met up again a few years later at a party. They didn’t recognize each other till they’d been dating a couple of months and Mom invited him over for dinner to meet her parents. When he saw the house he put it together.” I finished off the steps with a fuzzy haze of moss. “They never actually get moss on them, but I like the way it looks here.”

“Me too. And that’s a funny story.”

“The funniest part of it is that now he lives in the house where he did the crummy job on the steps. The top one is practically missing and we hop over it. Dad keeps saying he’s going to fix it, but he never gets to it.”

The bell rang for third lunch and I hadn’t finished the piece.

“Leave it here and you can work on it tomorrow.” Miss Downey stood up. “It looks like everyone could use another day.”

Lula took off her smock and hung it next to the door. “Come on, Juliet. I’m starving.”

* * * * *

Tammy, Lula and Jimmy all packed their lunches, so I stood in line alone until Pam came up behind me.

She tapped me on the shoulder. “Hey, Jules. Where are you sitting?”

“With Lula and Tammy. Over by the TV.”

“How’s Mark?” She always said his name with this little whimper.

My eyes rolled. “He’s fine.”

“It’s too bad he couldn’t come to the dance.”

“He’s a senior. Why would he come to a junior high dance?”

“You could ask him to chaperone next time.”

We shuffled forward. “He’s not old enough. You have to be eighteen, at least.”

“He’ll be eighteen soon.”

“Anyway, he’s too busy to chaperone dances. He dates. All the time.”

“Then he hasn’t found that special girl yet.”

I took a salmon-colored tray off the stack and put a half pint of chocolate milk in one of the squares. Macaroni and cheese. Mushy green beans. Peanut butter balls rolled in coconut. Gross.

“He’s four years older than you, Pam. It’s not going to happen.”

“That’s nothing. My mom is eight years younger than my dad.”

“Did they start dating when he was eighteen and she was ten?”

“I am almost fourteen. Mark is only three years older.”

“Almost four. Get over him.”

She followed me to the table and sat with her back to the television. The teachers hoped that showing us the news would make us interested in current events. Most kids ignored it, but it saved you if you couldn’t find someone to sit with.

Lucas Emberry sat at the table right in front of the screen and shoveled food into his mouth while he stared at the news.

“There he is.” Tammy looked past me with deer-in-the-headlights eyes.

My spine stiffened and a sort of sick, sort of excited feeling raced from my stomach to my knees and back again. The macaroni and cheese felt like a fist-sized wad of cotton in my mouth.

“Who?” Pam asked and leaned to look around me.

Lula looked, too.

“Don’t!” I spit bits of chewed-up noodle on her arm.

“Gross!” She flung it off and glared at me.

“He’s dreamy,” Tammy murmured. She reached across the table and grabbed Lula’s arm. “He looks dangerous, doesn’t he? I love that.”

Jimmy looked past me and scowled. “Who? Him?”

Pam nodded and propped her elbows on the table. She tapped her fingertips together and raised her eyebrows, as if she knew something the rest of us didn’t. “He’s the kind of guy who breaks girls hearts. I can tell.”

“His name is Damon.” Jimmy shook his head and went back to eating.

“You know him?” I blurted out.

Jimmy narrowed his eyes at me.

Tammy looked from Jimmy to me, and back again. “What do you know about him, Jimmy?”

Jimmy turned toward the TV and shoved a forkful of green beans in his mouth. “I know somebody was looking for him this morning.”

I could’ve kicked him. In both shins.

Tammy put her hand over her heart. “He’s coming this way! We should invite him to sit with us!”

Let him sit here!

My stomach twisted into a pretzel and threatened to make me hurl, like Linda Blair in The Exorcist.

No, make him go away!

Lula’s eyes rolled. “There goes Amica.”

I turned to look.

Damon stood just outside the serving line exit door. No leather jacket, and the Einstein T-shirt draped perfectly over his square shoulders and tanned arms. His scent filled my head and chest again as my mind plunged into its two memories of him like an Olympic swimmer off a high-dive.

Amica walked out of the food service door and stood next to him as she gazed around the cafeteria. She held her tray against her waist with one hand and twirled her diamond pendant with the other. She tipped up her chin and smiled at Bethany and Tori, as if she just noticed them at the table where they sit every single day. Then she leaned toward Damon and said something.

When her blond hair brushed against his forearm I wanted to tear a jagged chunk out of her perfect skin with my bare teeth.

He smiled at her and said something, but went to sit at a table by himself. He pulled a paperback out of his pocket and held it in one hand while he ate with the other.

“Whoa!” Lucas Emberry’s very loud yelp snapped my attention back to my side of the cafeteria. “Look at that!” He pointed to the TV screen.

The newscaster narrated over a shaky, grainy video.

“While filming a news segment on airport safety, a WAJE cameraman caught this astounding footage of a midair crash between two 737s. Six people are listed in critical condition at St. Martin’s hospital, but no casualties are reported at this time. Authorities are investigating the cause of the unprecedented breach of the planes’ respective airspace.”

On the TV screen two airplanes careened toward each other in slow motion. As one lifted off the runway another, coming in to land, slid in right behind the one taking off and clipped its tail on the way down.

When the video stopped at the airplanes’ point of impact, my head spun.

The very same picture hung on my bedroom wall.

CHAPTER 3

Mark heaped mashed potatoes on his plate and dropped the spoon into the bowl with a loud clank. AC/DC threaded out of his headphones and he bobbed his head in time with it.

Mom and Dad didn’t used to allow music at the table.

The portable black and white TV from the den now perched on the edge of the sideboard. Mom never put it away anymore. She turned her chair toward it and watched the news while we ate.

“Pass the asparagus.” Dad reached out one open hand, eyes still fixed on the fat, hardbound book wedged between his plate and mine. When no one else responded I reached across the table and moved the bowl in front of Dad’s hand.

I tapped Mark’s arm to get his attention.

He slid one foam-padded earpiece back, but kept nodding his head to the rhythm. “What’s up?”

“Can you help me with algebra tonight? I totally bombed the homework.”

“Sorry, kiddo. I’ve got a term paper and I have to pick Ginger up after cheerleading.” He popped the headphones back in place and yelled over his music. “Just follow the example problems at the beginning of the chapter. It’s eighth-grade algebra, not rocket science.”

I swirled my potatoes around on the plate then looked closer when something stuck to my fork. I tried a bite.

“Mom, what’s up with this?”

She swiped her tongue along the inside of her lower lip, then took another bite of pork chop.

“Mom.”

“What, Juliet?”

I moved into her line of vision. “What happened to real potatoes?”

She swiveled toward me. “I regret that dinner doesn’t meet with your expectations.”

Her expression shriveled my lungs into two quivery knots. “I was just joking.”

“And where were you when I was cooking? I didn’t see anybody else in the kitchen. No, that’s my job, isn’t it? I’m the maid and the cook and the chauffeur and the all-around Girl Friday, aren’t I?”

Some questions have no right answers.

Mark shot a quick glance at Mom and then at me before he closed his eyes and played an air guitar solo.

Mom turned back to the TV. “There’s nothing wrong with reconstituted potatoes.”

* * * * *

I closed my bedroom door, leaned back against it and stared at the sketches of Damon and the airplanes.

So weird.

Damon Sheppard. I whispered his name several times because I liked the way it rolled around in my mouth. Damon and Juliet. Juliet and Damon.

Right. Juliet never worked with anything but Romeo. Fat chance of meeting one of those this century.

Down the hall the shower started. Only Mark took showers in the afternoon and evening. And the morning and mid-day and before bed.

I sat down at my vanity and looked in the mirror. “You are no Amica Aldridge.” I picked up my brush and tried to stroke more length into my hair, but just made it frizzy. How far would I have to tip my head to the side to get the ends to flutter against Damon’s forearm?

Far enough to look more crippled than captivating.

What does Lucas even see in me?

Math. I had to do math.

I pulled my bag up onto the bed and flopped onto my stomach with my notebook and Elementary Algebra.

Damon still had that sketch of Mr. Hirschman. If Hirsch ever got hold of it I’d be dead. Maybe Damon threw it away. Hopefully he didn’t lose it. Or show it to anyone. At least it didn’t have my name on it.

Like anyone would wonder who did it.

He stuck it inside that awesome leather jacket, against the warmth of his body.

My sketch, nestled against his chest.

Homework. Two-variable equations.

Lucas would tutor me. He’d sit beside me at the kitchen table, then scootch closer and closer and slide his arm around the back of my chair. He’d move his mouth right next to my cheek and whisper linear equations into my ear.

I’d fail math first.

A rock hit my window with a loud crack. I rolled off the bed. Before I got there another one struck.

I opened the window. “You’re going to break the glass!”

Pam climbed up the sun porch roof. “Open the screen!”

“Why don’t you just use the front door?”

“Your dad doesn’t like me.” She squeezed through and landed with a thud.

“That’s because he keeps finding shingles on the ground.” I went back to my bed and Pam sat on the vanity chair.

“Guess what?”

I propped my head on one wrist and tried to focus on the first math problem. “What?”

“This is so cool!” She tapped her feet and wiggled in the chair.

I copied the problem into my notebook.

“My parents are going out to dinner the Saturday after next.”

“Yippee.”

She grinned that big, gum-baring smile of hers that made her buck teeth press into her lower lip. “I’m not going to have a babysitter!”

“Good for you.” I filled in the first line of calculation below the problem. At least I can get this far.

Pam slid off the chair and kneeled on the floor in front of me. “I’m going to throw a party,” she whispered.

I looked up. “Are you crazy?”

“It’ll be great! In two weeks I’ll be the coolest girl at Parnell Junior High.” She did a happy dance on her knees.

“Your parents will kill you.” I sat up and crossed my legs. “How can you possibly throw a party in the couple of hours they’ll be at dinner?”

“It’s a thing with my dad’s company. There’s an award ceremony and everything. They’ll be gone at least four hours.”

“You are crazy.”

“Will you come?”

“No.” I pulled my notebook onto my lap.

“I’ll invite Damon.”

My blood chilled. “So? Why should I care?”

Her eyes rolled up at the ceiling. “Please, Jules. You turned about eight shades of red when he walked into the cafeteria.”

That Jimmy knew was bad enough. Now Pam? “Shut up.”

“Oh my gosh!”

Pam stared at my bulletin board.

“You do like him! That’s totally what he was wearing today!”

“Oh, crud.”

“Don’t be embarrassed. He’s a fox. And I’m not going to tell anyone.” She stood up and went over to the wall. “This is really good. Why didn’t you draw his face?”

“I’m not his groupie or anything.”

“Cool airplanes. I saw the news. Why’d you do those?”

I took a deep breath and shook my head.

“What?” she asked.

My eyes started to throb and I rubbed them.

“Jules?”

“I drew those yesterday. Both of them.”

She turned to look at me. “Yesterday?”

I nodded. “Yesterday.”

“I don’t understand.”

“Neither do I.” I stood up and went over to the cork board. “I met Damon at the dance on Friday, kind of. I didn’t really meet him.”

“Heard about it. Bloody nose. Ick for you.”

“I started sketching him last night. It was stupid.”

Pam tipped her head. “So why the airplanes?”

“It was something Damon said.”

“At the dance?”

“No. Today.”

“But you drew it before, and it happened today? Just like the other one?” She sat down on the bed, but didn’t take her eyes off the sketches. “You swear you did these yesterday.”

“Swear.”

She smiled. “Draw something else.”

The bed bounced as I flopped down. “I’ve got to do this math.”

“Do it later.” She took my notebook and turned the page. “Here. Draw something you want to have happen. See if it works again.”

“That’s mental.”

She pointed to the wall. “So’s that.”

We looked at each other and I bit my lip. “I draw stuff all the time. This is the first time it’s been,” I searched for the right word, “predictive.”

“It’ll either work or it won’t. It doesn’t hurt to try.”

“What should I draw?”

She closed her eyes. “Draw Damon getting down on one knee to profess his undying love to you.”

“That’s stupid.” But maybe worth a try?

“Then do me and Mark that way.”

“Sorry. If I’m going to do this, I’ll do it with something that might actually happen.”

She lay on her side and propped her head up. “No. You should totally do it with something crazy, so if it comes true you’ll know you have the power.”

“The power?”

“The Power of Artistic Prophecy,” she said and waved one hand through the air.

The Power of Artistic Prophecy?

“Just try,” she pushed.

What could it hurt? “Okay,” I said, and I drew a line across the page. “Here goes.”

Pam scooted over beside me. “What are you doing?”

“Watch.” I did the outline of the school building, penciled in the windows and the letters on the front, and filled it in with the trees and bushes around the yard. Then I drew boards nailed over the front door in an X. I hung a sign beside the door, which read, “August 31: Closed for Repairs”.

“Awesome! No school tomorrow!”

I tore the picture out and tacked it to my board. “Don’t count on it.”

The bathroom door opened and Mark’s footsteps pounded down the hall. He knocked on my door and yelled, “See you later, kiddo!” then thundered down the stairs and out the door.

Pam dashed for the window. “I’ll see you tomorrow!” She threw open the glass and the screen and ducked outside.

“Where are you going?”

She called out to Mark as she slid down the sloped roof. “Can I have a ride?”

His back tires spun as he lurched out of the driveway.

Pam rode the roof to where the edge met the ground. Another shingle dropped off beside her. Her shoulders slumped as Mark got away, and she trudged home. I watched till she turned the corner and disappeared.

The morning paper still lay next to our front steps.

I squinted, leaned out through the open window, then climbed onto the roof.

No way.

I slid over to the edge and craned my neck to get a better look.

A greenish-gray tinge covered the top step, and spread over the edges of the others.

Moss.

CHAPTER 4

I dressed and redressed half a dozen times. Nothing in my closet worked. If not for the heat I’d have borrowed a flannel shirt from Mark to wear over stirrup pants. I finally settled on a knee-length, pleated navy skirt and a white short-sleeve, button-down blouse.

I sprayed and brushed my hair until it lay flat and stiff, then pulled back the sides and reached for Nonnie’s barrette. Her brother, my great uncle, gave it to her, and she used to put her long, silver hair up with it every day, before it all fell out. She gave it to me the Christmas before she died.

“Don’t ever lose this,” she whispered when I opened the box. She smiled, her face a beautiful, wrinkled landscape of life and pain. “When it pleases, love will awaken it, and you’ll see.”

She said a lot of nutty things during those last months, while the cancer and the chemo fought inside her.

I snapped the barrette’s catch open and something dropped, rolled to the edge of the vanity table and fell to the floor.

“Oh, crud.” Did I break it?

It landed next to my foot, and I kicked it out from under the table.

Long and thin, gold like the barrette, it looked like a tiny cylinder in two sections. The hinge?

I turned the barrette over in my hand and found the hinge still intact, but on the adjacent side of the clip lay a narrow channel, as though a second, longer hinge resided there. I picked up the fallen piece and laid it against the hollow. It snapped in.

Perfect fit.

With my longest fingernail I pried the cylinder out again and it fell onto the table. I swept my hair back and clipped it with the barrette, then examined the broken piece.

“Juliet!” Mom called up the stairs. “You’re going to be late!”

I dropped the gold bar into the front of my vanity drawer, then dug further back to find my tube of Strawberry Shortcake sparkle lip-gloss. I glazed my mouth with it and kissed at the mirror.

My skirt swished back and forth as I rushed down the stairs and slid into my chair at the table.

“Don’t you look nice?” Mom said. “What’s the occasion?”

“Nothing.” I reached for the cereal.

“Maybe a boy?” Dad said.

Mark pushed my shoulder. “About time.”

“Knock it off,” I said.

Dad put the newspaper down. “What’s his name?”

“There’s no boy.”

Mark sniffed me and poked my hair. “Three pounds of Aqua Rock. This is serious.”

I kicked him hard under the table and my big toe cracked. “Shut up!”

Mom waved her hand at Mark. “Leave her alone,” she said, then smiled at me with this strange look in her eyes. “Juliet’s growing up. First a bra, now a beau.”

“Geez, Mom!” I stood up too fast and knocked my cereal all over the place.

“A bra?” Dad choked. He turned to Mark. “Is she wearing bras now?”

We hadn’t talked so much at a meal since ever, but I’d have traded all the happy-family time on earth to be able to send the three of them straight to Siberia. Or Pluto.

I swiped the Cheerios off the table and back into my bowl. Cereal on the floor crunched under my bare feet.

“It’s nothing to be embarrassed about, Juliet,” Mom said.

“Maybe a boy will finally get her nose out of those sketchbooks,” Dad muttered.

“Howard!”

I dumped my cereal in the garbage.

“Why don’t you let Mark drive you to school, so you’ll have air conditioning?” Mom suggested.

“Yeah, I’ll take you. I’d like to get a look at the guy.”

“There’s no guy!”

I fled from the kitchen to the entryway, and then realized I had no shoes. None I wanted to wear, anyway.

I owned three sensible pairs of footwear: everyday sneakers, white flip-flops, and black patent-leather Mary Janes. We weren’t allowed to wear sandals to school, so that left the sneakers or the Mary Janes.

The Mary Janes were my church shoes, and Mom forbade me to wear them anywhere else. I didn’t like them much anyway. But Keds? With a skirt?

Then I saw them. Mom left her shoes by the door after her client interview yesterday.

“Here comes the bus!” Mom yelled.

I slipped them on, grabbed my bag, and stumbled out the door.

I’d deal with Mom later.

* * * * *

I turned my ankle getting down the driveway. On the bus three people commented on my shoes before I got to a seat. Then the spiked heel jammed between the floor vents and I had to scrunch down to work it free.

And the drawing did not come true. Though not surprised to find Parnell open, I was surprisingly disappointed.

My fingers clenched the railing as I picked my way down the school bus steps. The big toe I stubbed on Mark’s shin throbbed.

“Careful there, Juliet,” the bus driver cautioned. “Those are some clodhoppers.”

“Holy High Heels, Batman.” Pam whistled as she followed me off the bus.

“They’re my mom’s.”

“Does she know you have them?”

“Not yet.”

Pam’s eyes bugged out like Wile E. Coyote’s. “Your mom loves her shoes.”

“Yeah.”

Pam bit her lip. “She’s gonna kill you.”

By the time I made it to the top of the school’s front steps my calves felt like someone shredded them with a fork. In the halls my clack-clacking turned heads.

Hirsch closed the homeroom door behind us. “Good morning, Miss Martz. Miss Brynn, I see you’ve attained new heights.”

I passed between Tori and Bethany to get to my seat.

“Tori,” Bethany said, “I had no idea it was school uniform day.”

Tori giggled.

“And where did she get those shoes?” she added as I slipped into my seat. “Sleazebags R Us?”

I tucked Mom’s navy and rhinestone pumps under my chair.

Hirsch propped his feet on his desk and leaned back. “As we have no announcements today, let’s get started on the homework.”

Not me. Please, not me.

“Mr. Sheppard. To the board, please.”

Somewhere close behind me a chair scraped across the floor. Two steps put him beside my desk, and he dropped a folded piece of paper on my lap as he passed by.

How had I not seen him? I looked over my shoulder. Erik waved two fingers.

Of course. You couldn’t see André the Giant if he sat behind Erik.

Both of my hands clutched the paper he dropped.

A note. A very cute boy passed me a note!

Hirsch read aloud anything he seized during class, so I didn’t dare open it. I folded it in half again and stuck it in the zippered pocket of my bag.

Damon picked up a piece of chalk, wrote the problem on the board, and described the solution as he went along. Totally at ease in front of the class, he explained two-variable linear equations better than Hirsch ever did.

“He has the best voice,” Pam whispered to me. “Very deep and masculine.”

Shut up, Pam.

“I am absolutely inviting him to my party.”

Damon really got algebra. I flipped open my notebook and followed along.

“So after I solved for b, meaning I ended up with a ‘b =’ equation…”

That’s what it means to solve for b?

When Damon finished the first problem, Hirsch had him do the second one as well. I watched carefully and fixed my mistakes as he went along.

That makes total sense! Why couldn’t anyone else explain it like that? Duh!

I finally got it. I could’ve hugged Damon Sheppard, and not just because I’d like it.

After class I stopped at Hirsch’s desk. “Mr. Hirschman, I did all the problems in my homework wrong.”

“Yes, you seem to be having a fair bit of trouble.”

“But I get it now. Can I fix these and give you my homework after study hall?”

“We can’t keep doing this, Miss Brynn.”

“This is the last time. I promise.”

His mole wiggled as he scratched his stubble. “I want it before the third hour bell.”

* * * * *

I worked like crazy during study hall.

Erik looked across the table. “Good on ya, Juliet! Did you take my advice and get a tutor?”

“The way Damon explained it made complete sense,” I said, and hoped I didn’t whimper his name like Pam did Mark’s.

“Yeah, he’s a math whiz.”

“How do you know?”

Erik went back to charting animal species. “He nailed the math material at Academic Olympics practice last night. You should’ve come.”

“He’s doing the Olympics?”

“If he’s as good in other stuff as he is in math, he could just about be the whole team by himself.”

“I heard something about him having been in juvie,” I whispered.

Erik nodded. “Yeah, I heard that, too.”

“Do you think it’s true?”

He shrugged.

Drew Barony raised his head off the desk a few inches. “Can you guys keep it down?”

Erik pointed at him. “It lives!”

“Take a flying leap, Athaca.”

* * * * *

I dropped my work off at homeroom before English, and barely made it into my seat before the bell. Mr. Tollin read Anna Karenina at his desk. I unzipped the outside pocket of my bag and pulled out The Little Prince. Damon’s note dropped to the floor.

How could I have forgotten about it?

I put my bag on top of my desk and hid behind it. My palms started to sweat.

Calm down, Juliet. It’s a piece of paper.

It’s a piece of paper Damon Sheppard gave me. I closed my eyes, unfolded it, took a deep breath, then opened my eyes again.

My sketch of Hirsch.

But Damon wrote something at the bottom. I held it up and squinted to read the very small print.

“You nailed him. D.K.S.”

D.K.S. Damon K. Sheppard.

“Whatcha readin’?” Amica’s face peered over my bag.

I folded the note and stuffed it back in my bag. “Nothing.”

When she smiled, her pink lips curled up on both ends but her eyes never moved. “Doesn’t look like nothing.”

“Why do you care?” I opened The Little Prince and took out my bookmark.

“Didn’t you get your homework done?” She turned back to the front of the room. “Mr. Tollin! Mr. Tollin! It’s time to start class.”

If I ever got my sketches to prophesy again, I’d do one of Amica Aldridge with scabies and the creeping crud.

* * * * *

“Two steps up and two steps back, then lead your gal around the track!”

Why square dancing is part of the physical education program I will never understand.

I only saw Drew Barony awake and vertical during basketball games and gym class—the one course in which he exceled—and today he and the other guys competed to see who could throw his partner highest and/or farthest. Drew is not small and I am not large and I hated Miss Sweeney for partnering us alphabetically.

“Allemande right around the town, then spin your partner up and down!”

“Hang on, J.B.!” Drew yelled, then picked me up by the waist and heaved me over his head.

“Drew!” I clutched his denim-blue gym shirt in both fists as he spun me in a circle. “Not funny!”

“Mr. Barony! Mr. Peterson!” Miss Sweeney barked over the chipper twang of the caller on the square dancing record. “Mr. Athaca! Stop swinging the girls around!”

The loudspeaker crackled to life and the front office secretary’s bored voice echoed through the gym. “Coach Sweeney? Please send Juliet Brynn to the office. Her mother is here.”

Everyone in the gym hooted and whistled, as if a summons to the office meant execution.

Today, it probably did.

My gym uniform shoes squeaked against the speckled blue tiles as I hurried down the empty hallway toward the office. The round white clock with the needle-shaped hands tick-tocked as I passed under it.

JU-li-ET’S-a-BOUT-to-DIE.

A leather shoestring hung from one end of the wooden hall pass and I twisted it around my index finger till the blood pooled up in my knuckle.

Mom stood outside the office at the desk, drumming her acrylic nails on the counter. She spun toward me and pointed.

“Juliet Alexis Brynn, where are my shoes?”

“I’m sorry.”

“You’re going to be sorry. Those are brand new and cost a mint. If there is one scratch on them.”

I appealed to her sense of style, to the sisterhood of fashion anxiety. “I just didn’t have anything that looked right.”

She took two steps toward me. “You have all the shoes a thirteen-year-old girl needs.”

“Mom, I—”

“Go get them.”

I turned around and marched back toward the gym. My heart pounded in my chest and my temples, and I mashed the side of my T-shirt in my fist.

The girls’ locker room looked like the Gap stockroom exploded. I stepped over hot pink tennies and red Converse, piles of jean skirts and stirrup pants, pastel Henleys and tank tops. I picked my way to the bench where my skirt and blouse lay folded and my mother’s spikey, expensive heels waited under the seat.

I sat down and reached into the toe of the left shoe to get Nonnie’s barrette out. Wrong shoe. I picked up the other one and turned it upside down.

Where is it?

Every sweat gland in my body pulsed hot and cold as I searched for the barrette.

“I know I put it in here.” I tipped both shoes and looked inside. Nothing. I grabbed my blouse in one hand and the skirt in the other and shook them open. “Where is it?”

Miss Sweeney pushed the locker room door open with a loud thud. “What’s going on, Miss Brynn?”

“I can’t find my barrette.”

“Worry about your hair later. Get back in the gym.”

“I have to take these shoes to my mom. She’s waiting at the office.”

“You have two minutes.”

“Miss Sweeney, my barrette’s gone. It was my grandmother’s.” I searched through the scattered clothing near my spot.

“You shouldn’t have brought it to school if it was that precious. One minute, fifty-five seconds.” The door swung back and forth on its hinges then clicked to a stop.

I grabbed the shoes and hurried back to the office as fast as I could without running, a cardinal sin at Parnell Junior High.

Mom took the shoes and examined them. I prayed that the vent grate on the school bus hadn’t scratched them.

“If you ever again take something of mine without asking…”

“What am I going to wear the rest of the day? I can’t take these outside the gym.” I pointed at my soft-soled P.E. shoes.

“Be glad that I’m more thoughtful of you than you are of me.” Mom pulled my Keds out of her messenger bag. “You and I will have a long talk about this tonight.”

“I have to get back to gym.” I turned and walked away.

“You think about what your punishment is going to be.”

I bit the inside of my lip. “Why don’t you think about it?” I whispered.

* * * * *

When gym class ended I rushed back into the locker room to shower first and fastest. I kept an eye out as I buttoned my blouse and zipped my skirt, but the barrette never appeared. “Please, God,” I begged silently. “Let me find it.”

I slid my feet into the Keds. The threadbare padding under the heels and toes clung to my skin and stuck, then peeled off, then stuck again as I walked over to drop my towel in the basket. The knobby bones on both sides of my ankles jutted out like Dumbo ears.

The bell rang and girls raced out of the locker room. In one last desperate search, I checked under all the benches and inside every locker.

Mia Teele stood by the door with her lower lip between her teeth. Then Miss Sweeney pushed the door open and knocked Mia aside. “Get to your next class, girls.”

I bit my lip. “I can’t find my barrette.”

“I could help her look for it,” Mia squeaked.

“Your hair’s fine.”

I couldn’t leave. It had to be here. If I left, I might never see it again.

“Are you having trouble understanding English, Miss Brynn?”

“If you find it, please let me know.”

“If someone took it, it’s gone.”

CHAPTER 5

I slanted my easel toward the window to get the best natural light. But the morning’s cotton-ball clouds rolled toward the horizon, and a thick mattress of iron gray came in from every other direction.

Miss Downey looked out the window from her desk against the adjacent wall. “A perfect day for charcoal.” She leaned back in her seat, sketchpad on her lap, and propped her bare feet up on the register.

“Who do you think took it?” Jimmy sketched an outline of his latest superhero.

“Amica? I don’t know.”

“Doesn’t seem like her style. And she’s not even in your gym glass, right?”

“I feel sick.” I stared at the half-finished flower and steps on the canvas in front of me.

The moss.

That made three drawings I’d done that came true.

“Jimmy,” I whispered. How do I even ask something like this?

“Yeah?”

Deep breath. “Do you believe in ESP?”

He looked up. “You mean like mind-reading?”

I shrugged and dipped my brush in cornflower blue. “More like seeing the future.”

“Psychic powers?”

“Maybe.” I shaded the edges of a couple of moonflowers, then penciled in two more on a vine that stretched up from the ground.

“I guess not. I never really thought about it. Why?”

I made the highest moonflower arch up toward the tiger lily. “Sometimes things happen. Like I knew something was going to happen, then it did.”

“Like déjà vu?”

“Not exactly.”

Jimmy put his pencil down and leaned back in his chair. He crossed his arms. “Do you know why I can’t go to the Sci-Fi Festival?”

“Your parents want you to wait till you’re older.”

“Nah. I said that, but that’s not it.”

I raised my eyebrows.

“It’s because they think it’s unbiblical. Occult.”

“Occult?”

“Like, witches and demons and stuff.”

“But Sci-Fi is all superheroes and aliens, right? That stuff isn’t even in the Bible.”

Jimmy shook his head. “Which they say proves their argument against it. I’m not saying I agree with them. They don’t really like that I’m into comic books at all, but as long as I don’t put in magic and stuff, they let it go.”

“So you think psychic powers are evil?”

“I don’t know. I guess, just be careful. Don’t mess around with something you can’t handle.”

I twirled the paintbrush between my finger and thumb. “I’m not really messing around with anything. It just happens.”

“So you’re not trying to make stuff happen?”

“I did try. But it didn’t work.”

Jimmy shrugged. “Might be a good thing.”

The storm clouds parted just then and for a moment a shaft of sunlight splashed across my face.

“You know what Peter Parker says,” Jimmy said. “‘With great power comes great responsibility’.”

I drew in another moonflower, higher than the last, then rubbed it out. “Be honest. Wouldn’t you like to be able to predict the future? Especially if you could create it the way you wanted it?”

He shook his head. “That’s a lot of control for one person to have. Think of the damage you could do.”

“Think of the good you could do.” I wet a corner of a small sponge and smeared the blue until it faded.

Jimmy went back to sketching in his boxes. “But who knows what’s really good? Think about it. Is there anyone besides yourself you’d trust with that power?”

“I’d trust you.”

“Really.” He snorted.

“Really!”

He turned his pencil over and erased everything from one frame. “You don’t even trust me enough to admit when you’re into somebody.” He looked up, then looked past me and smiled in the weirdest way. “Hey, look. It’s Damon.”

I lobbed my wet sponge at his face and got him in the forehead. “Shut up, Jimmy.”

Then Damon’s voice pierced straight through me. “Excuse me, Miss Downey?”

Miss Downey turned toward the door. “Can I help you?”

“Mr. Holden sent me to pick up some tissue paper for science. He said you’d know about it.”

My skin prickled with this sweeping sort of shock, like electricity, searing me all over. Breath wouldn’t come, and my heart thudded like I just rode the biggest, scariest roller coaster in the world.

“Hey, Jimmy. Hi, Julie.”

He said my name.

He knew my name.

Sort of.

I have to turn around. I have to look at him, and I have to say something.

“Say, ‘Hi’, Juliet.” Jimmy smirked while he wiped off his forehead.

“There’s a stack of tissue paper there on the corner table. You can take all of it,” Miss Downey told Damon.

“Thanks. See you.”

I stood frozen till the sound of his footsteps faded down the hall.

“What’s wrong with you?” Jimmy asked.

Tammy and Lula came over from their desks. “He knows you?” Tammy accused.

I inhaled and the electricity rushed out of my pores. My legs threatened to buckle.

“Look how red her face is,” Lula said.

“Shut up.” I closed my eyes.

“It can speak,” Jimmy said.

“I am so stupid.”

I am so very stupid.

* * * * *

He sat at our table during lunch.

I tucked my ratty Keds as far under the seat as my knees would bend, and I tried again to smooth my hair down where the barrette and hairspray left a crispy crease that made the sides of my hair look like a matched set of broken sparrow feathers.

He got right to the point. “Erik said he asked you to do the Academic Olympics. How come you didn’t show up yesterday?”

Everyone stared at me and I couldn’t answer because of the huge chunk of hamburger in my mouth. I couldn’t swallow, either. I held up one finger and chewed.

Pam intervened. “Juliet’s not exactly Academic Olympics material.”

I frowned at her.

“Erik said she’s amazing in art and stuff.” He looked right at me and smiled.

There’s a dimple in his left cheek, just a smidge outside the corner of his mouth.

“I’ve seen her work.”

The burger inched down my throat like a hard, dry lump of clay. I grabbed my drink and sucked on the tiny straw, but the milk just pooled up behind the burger.

“You’ve got Kim for the English questions,” Jimmy said. “Why do you want Juliet?”

I tried to speak, then realized food hadn’t gotten far enough down, and some milk slid into the wrong pipe. I hacked milk across the entire table.

Pam jumped up. “Give her the Heimlich!”

I waved her off and motioned for her to sit down.

“Juliet, are you okay?” Lula reached over and slapped my back. Hard.

My esophagus tightened and the burger crept in the wrong direction. Please don’t let me throw up. Please, God, don’t let me puke in front of Damon Sheppard.

“Don’t pound on her. She’s breathing.” Damon put his hand on my shoulder. “Try putting your arms up.”

He’s touching me.

I lifted my arms into the air and the front edge of my chair tipped down, dumping my ribcage against the side of the table. I’d hidden my ugly feet too far under me and when my elbows came off the table I lost my balance. The pain in my big toe made me jerk it away from the floor and my chair skidded backwards as I flailed to catch myself.

Damon grabbed my arm and thrust his foot behind the chair’s front leg.

He stopped my fall, but my feet still rested on the tops of my shoes and my ribs supported most of my weight against the sharp edge of the metal table. I jerked down the arm Damon held and meant to grab the table. I missed and landed on his leg.

“Miss Brynn!” Miss Sweeney screeched from across the cafeteria. “Take your hands off that boy.”

Everyone in the room turned to look at me.

Silence.

Then Drew Barony wolf-whistled, and the room erupted in laughter.

I pushed myself up from the table.

Damon stood, too.

“No!” I hissed and held up my palm.

My legs wobbled as I navigated the room through a watery haze. Someone touched my arm as I passed.

“Sweeney’s a jerk.”

Lucas. Always on my side. I tried to force my mouth into a smile for him, but my lips quivered as badly as my limbs, and a tear slid down between them.

I didn’t care about the rules. I ran.

Inside the girls’ bathroom I locked myself in the handicapped stall, sat down, hunched over my knees and sobbed.

* * * * *

Kitty’s letter waited on my bed. I picked it up and checked the postmark. Yesterday. How did a letter make it so far overnight?

I rubbed it between my fingers. Several long, flat lumps slid around inside.

My bag slid off my shoulder to the floor and I tore open the envelope. A sweet smell, like ginger ale and mint-chocolate cookies poured out. I dumped out the contents of the envelope and several silver-wrapped sticks of gum slipped from the folded pink paper.

This was the cool gift? Gum?

Dear Juliet,

Yesterday we went to an art thing at the fairgrounds, and I saw the coolest painting. I wondered if you could do it on an envelope for me?

In the painting there was a hawk, sitting in a tree under the moon. It was winter, and a tiny chipmunk ran around the shadows on the ground. The hawk stared right at the poor little thing, and you knew he was about to dive on it. I wanted to scream for the chipmunk to hide, quick, before the hawk attacked. I knew it would attack, because that’s what hawks do.

Do you know what today is? It’s the fourth anniversary of us becoming pen pals! I saw your grandma in her yard yesterday, when I was waiting on the school bus, and I told them we’re still writing. They said to tell you hello, and that they miss your grandma.

We’re going up to the lake next week. I’m so glad our schools don’t start as early as yours. Of course, you’ll get summer earlier than I will next year. George told me he’ll take me canoeing for a whole afternoon, and he’ll show me where he found a huge patch of blueberries up the river last year. We’ll have to paddle hard to get there, but coming back will be a breeze. I hope Mom and Dad let me go with him. Why are parents so much less worried about boys than girls? Is it that way with you and Mark, too?

I’m sending five sticks of my favorite kind of gum. It’s special, and I know you’re going to like it, too.

Have a great week, and don’t let things get you down. I like you, and so do a lot of other people.

Love, Kitty

I lined up the five sticks of gum in a row on my pillow. A little longer and wider than any other kind I’d seen, they almost looked like microscope slides. Their wrappers shimmered in the afternoon sun, kind of whitish, but also silvery, sort of metallic like foil, but sort of not, too. I slid my fingernail along the side until it found the edge of the paper, then peeled one partway open. The paper felt crackly, like onion skin. I folded it back up and the seam disappeared again.

Sugar to Mark was like blood to a shark, so I restacked the sticks of gum and looked for a place to hide them. I unzipped the inner pocket of my canvas school bag and stuffed them between two maxi pads. Mark would never dare to look there.

I like you, and so do a lot of other people.

The humiliations of the day swirled around me.

I covered my eyes with my hands, then raked them through my hair. It felt like a mass of thready, crispy French fries.

I went down the hall to the bathroom I shared with Mark and locked the door. The showerhead pointed almost directly at the opposite wall, so I tipped it down before I turned on the water. I took off my stupid clothes and stuffed them into the hamper.

“What is wrong with me?” I stood in front of the mirror and tried to figure it out.

Nothing looked wrong, really. My nose wasn’t too big or too small. My hair was a little fine and sometimes frizzy, but could be a lot worse. I didn’t have cropped, kinky fuzz like Martha Harner, or Mia Teele’s stringy, shaggy mane of split ends that fell down to her behind and always looked like an enormous bird’s nest.

I didn’t hate my eyes. Slate gray with dark blue rims.

My lips looked all right.