Description:

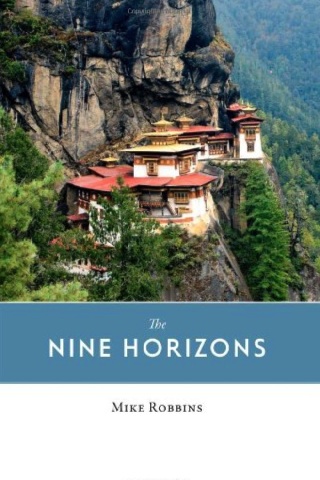

In 1987 Mike Robbins, a young journalist in London, felt restless and decided to travel. He never really stopped. In the quarter century that followed he lived and worked in countries as diverse as the world itself. The pieces in this book take the reader from rural Sudan to the headwaters of the Amazon, from Semana Santa in Quito to Buddhist temples in the Himalayas, across Bhutan on a motorbike, into the ancient souk of Aleppo, to the steppes of Central Asia and finally to New York. Along the way there is Ethiopian gin, a sex tourist in Moscow, Kyrgyz women in cycling pants, a surreal toilet in Brussels, echoes of slavery in Brazil, and an encounter with Helen of Troy in Third Avenue. The Nine Horizons is an anarchic snapshot of a troubled but beautiful world in transition.

Book Rating: PG

e x c e r p t

The Nine Horizons

We were late leaving Delhi. The apron was empty, baking in the heat. The day before we had hired a tuk-tuk, one of those gimcrack three-wheelers in which the driver sat ahead and the passengers on a narrow bench behind. A small two-stroke engine popped and farted below us as we drove to Lutyens’s huge capital, the dome shivering in the heat, the reddish stone hot to the touch. It had been about 47 deg C and the mid-morning sky had been hazy and ill-defined.

I gazed out over the wing. A small, elderly Russian transport taxied by, complete with gun turret under the tail; it had seen better days. One of a small armada that set out from the former Soviet bloc in those years (it was 1992), packed with enormous women in old-fashioned headscarves with things to sell and things to buy; a tramp-steamer of the skies, the air around its exhausts distorted and liquid.

I began a conversation with a well-dressed man in the seat beside me. We had the same destination. I would be a development volunteer. He was an Indian diplomat. He had just finished three years in Kuwait.

“How was that?” I asked him.

He thought for a moment. “Imagine a supermarket in the desert,” he said.

A companionable silence followed. I picked up one of the newspapers that the cabin crew had draped across the armrests, expecting The Times of India. But it was their own national newspaper, Kuensel. A banner headline ran across the front page: GUPS CALL FOR ACTION ON NGOLOP PROBLEM.

I wondered if the Indian diplomat could tell me what a gup was, or indeed a ngolop; but he was dozing. In fact, a gup is a village headman or representative. As to the ngolops, I would find out soon enough.

A cabin attendant passed by, looking right and left to check belts. She was tall—unusually so—and had a broad Asiatic face with very high cheekbones and golden-brown skin, and a curious lack of expression. Her thick black hair was cut in a bob. She wore a lightweight waist-length silk jacket over what looked like a sleeveless wrap. The wrap, called a kira, ran from her chest to her ankles, and formed a sort of tube, leaving little obvious room for movement; it was secured with attractive gold fasteners on her shoulders. Below the wrap was a smart white blouse.

We climbed away from Delhi and across the arid North Indian plain. Lucknow slid below us and we turned gently east. After an hour or so, bright white clouds started to line the horizon to the left; as we neared them, they took firmer shape, for they weren’t clouds. We kept them to starboard a while, then drifted slowly across them, and I saw white points and cascades of rock and deep grey-green defiles. The mountains were shrouded here and there by a little cloud—thin as yet, for the monsoon was barely beginning.

Before long, the peaks came closer as we sank into a valley. Later, pilot friends would tell me how, in the monsoon months, they would cruise above the clouds, looking for a hole that was large enough for them to nip through, take a look around, and nip out again in a hurry if there was anything in the way. If there wasn’t, they would guess which valley they were in, and guide the four-engined jet through it into the right one so that they could find the airstrip, ready to yank the stick back and pop porpoise-like above the clouds again if they ran out of space, or got lost. (Once above the clouds, landmarks such as Kanchenjunga and the Jomolhari range, and the Tibetan plain behind it, would soon tell them where they were.)

The approach itself was difficult. As we began it, the valley slopes moved up towards the plane’s belly. A structure strange to me but clearly a temple of some kind slid below us, wisps of cloud reflecting the sunlight. The peaks were above us now, although we were barely 60 miles away from the blistering Bengal plain. The temple disappeared behind us and we catapulted over the edge of the mountain on which it stood, then dropped like a stone; my stomach flew upward. Later, I would arrive one windy winter’s day when the plane would drop into an air-pocket, so shocking us that my neighbour, an urbane and charming acquaintance of royal blood, shrieked and dug her fingers so deep into my arm that it was bruised for a week. Today was smoother. We glided into a deep, rich valley ablaze with agriculture, and as the plane flared and settled, we drifted past a mighty building, half-temple, half-castle, a magnificent riot of white walls, hardwood windows, shingled roof and gilded gargoyles.

We filed down the steps and into the sudden calm of the strange spring morning. There was a small road a few hundred yards away, but nothing moved on it. On either side, the valley was lined with steep slopes, partially forested; the soil between the trees looked light and sandy. It was warm, but much cooler than Delhi, and there was a light breeze. At the far end of the runway, the temple/castle, Paro Dzong, dominated the narrow valley. Nearer at hand was a low wooden terminal. In it we queued before a man wearing what looked like a cross between a dressing-gown and a full-body kilt; the top was loose, voluminous, and I had heard that one could carry six bottles of beer within, kept in place by one’s belt. The garment was the gho, the male equivalent of a kira, and was worn at all times, by law, when more than 300 metres from one’s house. Across his shoulder was a cumney; this was a cross between a shawl and a scarf and was white – unless you were a dasho, which loosely speaking meant a knight of the realm; then it was red. A member of the national assembly wore a purple cumney. The King and his spiritual counterpart, the Jhe Khenpo, wore saffron ones.

A stamp was thrust onto a blank page; a large, round, purplish-blue stamp, with Tibetan script around the outside, a row of auspicious symbols such as conch shells, and finally, the words GRATIS VISA. SEEN AT PARO. I went out to join the tourists, smug in the knowledge that whereas they paid up to $200 a day for the privilege of visiting the country, I had won that most elusive prize: a resident’s permit for the Kingdom of Bhutan.

*** *** ***

One of the world’s smallest capitals, Thimphu had a population of 31,000 then; today, I believe, it is three times that, but in 1992 it had the air of a small country town, the sort you drive through now and then in England when the motorway is blocked and the police divert you. The difference was its dramatic location, in a very narrow valley at 7,500ft; from its edges, steep slopes rose to peaks twice that height, their summits shrouded in the mist and rain of the monsoon season that was just beginning. The lost valley.

I soon explored Thimphu. In truth, there was not much of it then. There was a long main street that started at the top of a hill, and ran for about a mile and a half. It was punctuated by three little traffic islands. There were no traffic-lights; instead, at these three junctions, handsome little wooden pagodas sprouted from the concrete, complete with the appropriate traditional decoration. In each one, at busy times, there stood a smartly-dressed policeman in a blue, Western-style uniform, directing the traffic with stylised gestures, the balletic grace of which was enhanced by immaculate white gloves. In the early hours of the morning a year or so later, two friends and I emerged from a private bar a hundred yards or so from the central island, well the worse for wear. The street was deserted. My friends made straight for the nearby island and began to walk clockwise about it as if it were a religious structure, chanting Om mani padme hum – Behold the Jewel in the Lotus. I then leapt into the pagoda and started to direct imaginary traffic with extravagant hand-gestures. After a minute or so we became aware of a white-gloved policeman standing on the corner, his face a mask in the moonlight. We fled.

The main street was lined with low wooden shops, each with a front partially open to the street. They seemed, for the most part, to sell much the same thing; plastic implements, packets of tea, rather hard soap, chilies, and, for some reason, dried fish – always dried fish, although I never saw anyone buy any. However, Shop No. 9 had beer, while Shop No. 6 was good for potatoes. Here and there were different types of shop; a butcher for instance. And there was a small but very well-kept public library halfway up the street, with an excellent selection of old English-language paperback novels. It was run by a charming young woman who appeared genuinely embarrassed when I returned some books a week late, and she had to make me pay a few pence in fines.

Nearly opposite was the national bank, which was helpful but not easy to use. One entered from the small car park to find oneself in a dark banking hall with wooden floors; as in India, guards lurked in the gloom, nursing ancient rifles. The banking counters took the form of grilles with tiny apertures, like old-fashioned ticket-offices; behind, one could see shirt-sleeved Indian clerks and their gho-clad Bhutanese colleagues writing with pens in huge ledgers. In 1992 there were no computers of any sort in the building at all, so far as I was aware. Withdrawing money involved fighting one’s way to the head of one queue, presenting one’s papers, taking a brass counter and then joining the crowd jostling and heaving around the window on the other side, waiting to hear the number on your counter called out so that you collect a pile of rupees (if travelling) or ngultrum, the local currency. This would happen when the clerk on the first desk got around to bringing the record of his transactions across, usually every 15 or 20 minutes. The bank staff were pleasant, but it was chaos.

There were few other shopping facilities in Bhutan. There were one or two shops where one buy could cassettes of Hindi film music, which was popular, or blank tapes, again Indian; these were mostly good, and not expensive. You could also buy some non-Bhutanese clothes and there were shoes too, but the selection was limited and expensive. A few shops stocked Indian magazines and newspapers, including filmi magazines that reported the doings of Bollywood; these were often in English. Starved of glamour, I bought a few myself. At the time, television was forbidden in Bhutan, but videos were everywhere and Hindi Bollywood movies all the rage. (The video shop sold filmi magazines. One day I saw two monks staring through the window at the cover of a magazine, the headline on which screamed EXCLUSIVE FIRST PIX JAMES DEAN SEVERED HEAD.)

When it came to restaurants, Thimphu was better supplied. The local ones served emma datse, the national dish, made of cheese and burning-hot chilies; I never came to terms with this, but there would also be dhal bhat and perhaps momos. The latter were little dumplings filled with meat, usually pork (occasionally yak, although I only encountered this once, in Sikkim). Or paksha-paa, which was pork (both lean and fat – the Bhutanese made little distinction), with the inevitable hot chilies, served on a large pile of savoury red mountain rice. The pigs had eaten well. Marijuana grows wild over much of Bhutan; Bhutanese people strongly disapproved of its consumption by humans, but used it as fodder. Some schools kept a pig, and small boys and girls in ghos and kiras trotted cheerfully towards the pigpen with armfuls of weed. The pork was excellent.

Western food was also served in a surprising number of places. There were a lot of short-term foreign consultants in Thimphu, and many were not there long enough to get into cooking. The best restaurant, 89, was a little expensive for volunteers but served good food, including excellent chips; I was told that some Irish volunteers, horrified by the soggy chips, had marched into the kitchen and showed the staff how to make decent ones. In 89 you could have a good yak steak in season – that was when the yaks came down to winter pasture just above the town. Yak was a little gamier and tougher than beef, but pleasant enough. On winter weekends I always enjoyed a long mountain walk, or bicycle ride, in the bright, crisp sun, followed by an evening meal of yak and chips at 89. By the time I left, there were several rivals, but none were quite as good.

I often took my evening meals in Benez. This was a small restaurant-cum-bar next to the guest house, on a side-street; it had perhaps eight tables for four, bare and unadorned, but with a small but rather cosy little bar at the back of the room. It was run by Dasho. Dasho really was a dasho, or knight; it is an honorific borne by provincial governors and others those who serve the King at high level. Dasho had been a very senior Government official, but he was an ethnic Nepali, and when the political situation worsened in the late 1980s (of which more later), he had had to leave his post. So he opened a pub instead. However, he was friendly and cheerful, and I never heard him complain. A short, bullet-headed, bald man in his 50s, he ran Benez (even he did not know where the name came from) with his wife, who sat behind the comfortable little bar in a friendly fug of cigarette smoke.

Benez had plenty of booze. There was bottled beer of different types. The best was Kalyani Black Label from India. Dasho normally had plenty but if he hadn’t, there was always a Sikkimese beer with a green label called Dansberg; it was not as good, but it served. Rarely, one might have to resort to Golden Eagle (or weasel’s piss, as a friend once called it). This had a disgusting soapy taste, but for some reason the Bhutanese liked it. If you couldn’t face weasel’s piss, there was also He-Man 9000, Sikkim’s answer to Special Brew. I could not take either weasel’s piss or He-Man so I would sometimes be forced to drink spirits. These do not agree with me, but I would enjoy a Dragon Rum sometimes. This was a refreshing local rum which came into its own in winter, and it was very cheap, I think the equivalent of about 10 pence a shot. Or one could have Bhutan Mist. This was a truly excellent Scotch distilled locally (the Scots had helped, I think). The local spirits all seemed to come from something called the Army Welfare Project in the southern town of Geylegphug.

Dasho was very hospitable and informal; one might forget he was a Dasho, were it not for the red cumney that he put on before getting into his white Premier Padmini to visit some Government office or other. (I cannot remember him wearing a ceremonial sword, however; perhaps only serving Dashos wore those.) From time to time he would sit and chat. I cannot remember him ever talking politics, and I never asked him to.

But I do remember one conversation we had during the monsoon, not long after I had arrived in Thimphu. It had been a damp, overcast day, and now the rain was sheeting down the windows; I had run here from my flat just behind, my evening reading, a tatty found copy of The Master and Margarita, held close to my shirt. Benez was quiet, one or two people sitting at the back table; Dasho’s wife sat peaceably behind the bar on her high stool, her cigarette-smoke curling into the soft light above her. Dasho sat opposite me, nursing a Dragon Rum. For some reason we fell to discussing local beliefs. Quite suddenly and calmly, he said that he had once seen a dragon.

I blinked. There was no hint of a smile on his face. “When was this?”

“I was doing my military service. In the 1960s.”

“Where?”

“Oh, in the mountains. It was at dusk. Dragons fly at dusk.”

“What did it look like?”

“Strange colours.”

No Bhutanese wishes to see a dragon; they are bad luck, and I sensed that Dasho did not much want to be pressed on the subject. In any case, at that moment my food arrived, and he excused himself; he never raised the subject again. Dasho was a professional man and widely-travelled; he was either telling the truth or testing my credulity, and to this day I do not know which.

*** *** ***

Aside from the centre, there was little to see in Thimphu. Even the majestic Dzong, and the majority of the government offices, were not in the town itself but a mile or two to the north. In fact, Thimphu was a bit claustrophobic. So far I had hardly had a chance to leave it.

I wanted a bike. This was partly for exercise, but also because I like bikes and wanted to explore the area. One could buy bikes in Phuntsholing, the southern border town at the foot of the mountains where they met the Bengal plain. But they were similar to English machines of the 1930s, being very upright and very heavy, with rod brakes and a single gear. I wanted something a bit more modern, or a gearbike, as the Indians called them. I mentioned this to another volunteer, Ken, who said a friend was thinking of doing the same, and he would mention it to him.

I forgot about it until two months later, in September. It was, for once, dry and bright; one of those rare days during the monsoon when it stopped pissing down, the concrete walls stopped turning green with fungus for a while, and the clouds drew back off the wooded hills round the valley, revealing the mass of prayer-flags clustered below the radio-mast on the hill to the west. I had been walking around Thimphu. I was passing Benez in the early afternoon when a horn hooted behind me. I turned to see Ken and a friend in a blue Land-Cruiser. “We got something for you,” said Ken. In the boot was a very smart red-and-white five-speed racing bicycle. The friend, Padraig, had indeed gone to Siliguri in West Bengal to get his Indian gearbike, and, hearing that someone else wanted one, he had kindly bought an extra one. It had cost about £38 (about $55) and was called a Hero Hawk.

I loved it, but it was heavy and needed tender loving care. The first fault I found was that the control cable for the derailleur was too short and would change the gears to low ratio, but would not allow the opposite movement. The cones that held the ball-bearings into the axles were loose, too, and one of the brake hoods moved around. A borrowed spanner and screwdriver proved enough to fix most of this, and I chopped up an old brake cable cover for the gears. The valves, like prewar British ones, had rubber in them. They would not mate with a modern pump, and the Indian adaptors could not cope. Eventually I got a plunger-pump from Siliguri. This consisted of a stainless-steel cylinder with feet that folded out at the bottom; the long plunger was topped by an elegant polished wooden handle. These were much used by rickshaw drivers in India, and were very effective. Lights were another problem. Bhutanese policemen confiscated bikes without lights at night. Someone who was going to Phuntsholing kindly brought back an Indian dynamo set. This lit up the street like a Roman candle but produced far too much power, so that as soon as one got to a certain speed the six-volt front bulb blew, leaving one careering down the main road from the Memorial Chorten in total darkness, wondering how far away the drainage ditch was.

Ken had a bike too. He left Bhutan on it that November. He had been helping in a Phuntsholing factory making plastic piping, but competition from India was fierce, and orders few. Moreover he had lived on the border through the worst of the civil disturbances that marked those years, and had had an eight o’clock curfew; there was little to do in Phuntsholing anyway. But he stayed for most of the two years, and then decided to go home his way, cashing in his air ticket, and hanging a saltire on his bike, on the crossbar of which he had written BHUTAN-SCOTLAND. With another friend, I accompanied him for the first 20 miles one soft Sunday monsoon morning and we waved goodbye, the saltire waving bravely from his rear carrier as he disappeared into the distance. He covered much of the subcontinent before Iranian visa difficulties forced him to give up the following spring.

A young Danish friend was even more ambitious. He bought two sturdy ponies and announced that he was trekking back to Denmark. In the summer of 1993 he set off from Thimphu, and crossed the Bengal plain to the borders of Nepal; but a robbery, and sickness in the ponies, forced him to give up in Kathmandu.

*** *** ***

The bike let me see something of the countryside. Bhutan is one of the most beautiful countries on earth, but there is little view from the Thimphu valley. The surroundings are wooded hills; no snow-peaks can be seen. For that, one had to climb 3,000ft to the 10,500ft pass of Dochula, a long and steep journey. Even there, there was nothing to see in the wet season, for the whole country would be shrouded in mist. Alternatively, one could climb on foot up the high mountains flanking the Thimphu valley, reaching a plateau at about 14,000 ft from which there were views of the high Himalayas that surrounded us. But I did not know that then; besides, I did not know the footpaths, and had the brains not to wander around strange mountains on my own. There were bears and boars and mudslides, and tree-roots that could twist your ankle and leave you stranded on a path that no-one might use for days to come.

Still, I could ride to the head of the Thimphu valley, through woods and along steep roads adorned with chortens, sacred monuments that contained Buddhist relics. After a few miles one reached the point where the last cart-track ran out. Here there was a traditional covered bridge across the rushing blue-white river, the Thimphu Chu, and the beginning of the yak-and-donkey path that led up a narrow gorge to Tibet, two or three days’ walk to the north. Now and then lines of men with pack-ponies would appear at the foot of the valley, laden with simple goods – tea urns, green plimsolls – that they had traded with the Chinese guards on the frontier.

Going south from Thimphu instead led one eventually to the Confluence, where two rivers met; one either turned right for Paro or went straight on towards Phuntsholing and the Bengal plain. However, 20 miles or so out of Thimphu there was an earlier turn to the right, a tarmac road which ran along the Gidakom Valley; narrower than the Thimphu Valley at the latter’s widest, but wide enough for agriculture, a couple of villages and a small lumber yard. The villages also contained the Leprosy Mission, then run by Danes. In the 10 years of its existence it had made such good progress against the disease that it was being run down. The road petered out after about 10 miles, and a track continued to a far-distant lake in the mountains. I liked riding through the Gidakom Valley; when the sun shone, the buildings shone white-and-brown, and when the chili harvest came, the crop was left drying on the rooves, bright red against the white houses and the deep blue sky. Sometimes one whooshed through a ford and then across the crops that covered the road; they were put there so that cattle-hooves and vehicles would thresh them.

Riding along the main road to the Confluence, I would sometimes pass what looked like public toilets in the middle of nowhere. They were corrugated-iron sheds divided into three cubicles, each one about eight foot wide and about the same depth. Often one would see one of the Indian road labourers hanging around near them, often Bengalis wearing their characteristic dhotis. These were their homes, and as far as I could see, the entire family squeezed into these and managed as best they could. I do not know where they got their food; perhaps it was brought up from the plain by their employers, but more probably they had to buy it on the local market like everyone else. I believe they were paid about 15 rupees a day – about 30 pence. In Bhutan, as in any subsistence agrarian economy, there was little labour to spare, and these Indians were essential for road maintenance. The sight of one of these families going slowly and joylessly about their business by the side of the road in the monsoon murk put one’s own troubles into perspective.

*** *** ***

In 1992 the monsoon ran an extra month, right to the end of October. But bad things, too, come to an end.

One Saturday afternoon at the end of the month, I set out on my bicycle, intending to ride up the road towards Dochula. The weather was good, and just after one in the afternoon I rode down the main road to India as far as the majestic Simtokha Dzong, the beautifully-proportioned 14th-century castle about five miles south of the capital. It was here that the Thimphu valley widened out, and Simtokha Dzong commanded a view of it. It was now an ecclesiastical school. When one passed its elegant form, one knew that one had left or entered the area of the capital.

Past the Dzong, I swung round to the left, into a side-turning. This was not quite wide enough for two ordinary cars. In fact, it was the lateral road which connected West and East Bhutan. The most important city of the East, Tashigang, was two long days’ drive along this road. First it snaked its way some 12 or 15 miles up to Dochula, the 10,500ft pass that led out of the Western valleys.

I did not think to reach Dochula. But I suppose I just never stopped. I could feel the warm sunlight on my back, but it was friendly, not oppressive. Looking up, I could see ridges of pine trees against the clear sky, and the road was dusted with pine needles. There was a warm, gentle scent. The road ahead wound upwards so steeply that the next two or three bends were stacked almost vertically above my head, the battlements of the concrete retaining walls clearly visible. There was no traffic, aside from the odd jeep-taxi, and the air felt soft and clear. Below me a valley started to deepen, dotted here and there with isolated farmsteads. Sometime in the late afternoon, I struggled up a last short slope to find the road dividing around a long prayer-wall; there were prayer-flags everywhere, and I realized that this was a place of note. I freewheeled to the left of the prayer-wall and onto a small meadow tufted with weeds. I was exhausted, and it was a moment before I lifted my eyes to the horizon, and saw a sight of such beauty that it was almost beyond the human eye. Below me, looking east, the hills tumbled one upon the other into the far, deep valley of Wangdi and Punakha, 6,000ft below. Beyond that, the ramparts rose again, rows of mountains speckled with fields, meadows and patches of forests, trailing off into a distant blue sky. Then I looked left, and realized that I was looking north into the frontiers of Tibet; distant white pinnacles were shrouded with wisps of cloud against a deepening blue, and nearer at hand was a great snowpeak with a strange, flattened, four-corner summit: Masangang. I was to see it from closer to, some months later, and think it one of the finest in the Himalayas.

I stayed there for perhaps an hour, until the shadows rising from up the valley warned me that there was only an hour or so of daylight left. Already a stiffening breeze was chilling me slightly through my shirt, and soon it would be cold. Reluctantly I started down the hill for home. Instead of the two or two-and-a-half-hour climb, I had a 40-minute run down the mountain, twisting around steep, cambered corners slippery with pine-needles and cow-dung. The light faded quickly. Every now and then the shadowy shape of a jeep or minibus would appear suddenly around a bend, causing me to heave on the cheap pressed-steel brakes; these barely worked, and I would sometimes cut past with inches to spare. Then a long straight appeared ahead, and I shot down it at perhaps 40 miles an hour towards the shapely shadow of Simtokha Dzong, looming above the road against the last of the light. The paddy-fields of the Thimphu Valley drifted into view, and then, as I rounded the corner, there was Thimphu, looking more than ever like a woodcut of Middle Earth with the first lights glimmering and the white and gold curves of the main monument, the Memorial Chorten, clearly visible. I shuddered to a halt as I reached the main road, and I think I was laughing.